We’re excited about the expansion of MediaBugs.org, our service for reporting errors in news coverage, from being a local effort in the San Francisco Bay Area to covering the entire U.S.

We’re excited about the expansion of MediaBugs.org, our service for reporting errors in news coverage, from being a local effort in the San Francisco Bay Area to covering the entire U.S.

But with this expansion we face an interesting dilemma. Building a successful web service means tapping into users’ passions. And there’s very little that people in the U.S. are more passionate about today than partisan politics.

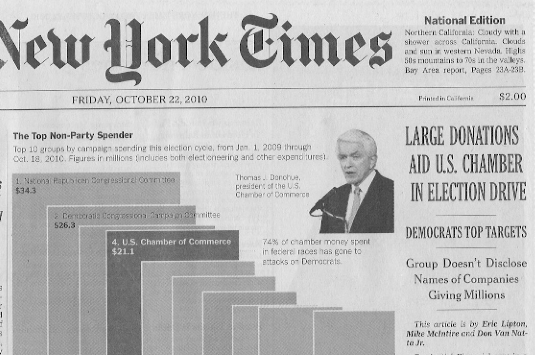

We have two very distinct populations in the country today with widely divergent views. They are served by separate media establishments, and they even have their own media-criticism establishments divided along the red and blue axis.

So the easiest way to build traffic and participation for a new service in the realm of journalism is to identify yourself with one side or the other. Instant tribe, instant community. Take a red-state pill or a blue-state pill, and start watching the rhetoric fly and the page views grow.

I’m determined not to do that with MediaBugs, though it’s sorely tempting. Here’s why.

I don’t and can’t claim any sort of neutrality or freedom from bias as an individual, and neither, I believe can any journalist. Anyone who reads my personal blog or knows my background understands that I’m more of a Democratic, liberal-progressive kind of person. This isn’t about pretending to some sort of unattainable ideal of objectivity or about seeking to present the “view from nowhere.”

Instead, our choice to keep MediaBugs far off the red/blue spectrum is all about trying to build something unique. The web is already well-stocked with forums for venting complaints about the media from the left and the right. We all know how that works, and it works well, in its way. It builds connections among like-minded people, it stokes fervor for various causes, and sometimes it even fuels acts of research and journalism.

What it rarely does, unfortunately, is get results from the media institutions being criticized. Under the rules of today’s game, the partisan alignment of a media-criticism website gives the target of any criticism an easy out. The partisan approach also fails to make any headway in actually bringing citizens in the different ideological camps onto the same playing field. And I believe that’s a social good in itself.

It would be easy to throw up our hands and say, “Forget it, that will never happen” — except that we have one persuasive example to work from. Wikipedia, whatever flaws you may see in it, built its extraordinary success attracting participation from across the political spectrum and around the world by explicitly avowing “a neutral point of view” and establishing detailed, open, accountable processes for resolving disputes. It can get ugly, certainly, in the most contested subject areas. But it seems, overall, to work.

So with MediaBugs, we’re renouncing the quick, easy partisan path. We hope, of course, that in return for sacrificing short-term growth we’ll emerge with a public resource of lasting value. The individuals participating in MediaBugs bring their own interests and passions into the process. It’s the process that we can try to maintain as a fair, open system, as we try to build a better feedback loop for fixing errors and accumulate public data about corrections.

To the extent that we are able to prove ourselves as honest brokers in the neverending conflicts and frictions that emerge between the media and the public, we will create something novel in today’s media landscape: An effective tool for media reform that’s powered by a dedication to accuracy and transparency — and that transcends partisan anger.

I know many of you are thinking, good luck with that. We’ll certainly need it!

Crossposted from MediaShift Idea Lab and the MediaBugs Blog