Of course it’s a bubble! Let’s not waste any time on that one.

The fact of a bubble doesn’t mean that all the stuff people in tech are building today is worthless, nor will it all vanish when (not “if”) the bubble deflates.

It does mean that a certain set of reality distortions infects our conversations and our coverage of the industry. If you are old enough to have lived through one or more previous turns of this wheel, you will recognize them. If they’re not familiar to you, herewith, a primer: three lies you will most commonly hear during a tech bubble.

(1) Valuation is reality

When one company buys another and pays cash, it makes sense to say that the purchased company is “worth” what the buyer paid. But that’s not how most tech-industry transactions work. Mostly, we’re dealing in all stock trades, maybe with a little cash sweetener.

Stock prices are volatile, marginal and retrospective: they represent what the most recent buyer and seller agreed to pay. They offer no guarantee that the next buyer and seller will pay the same thing. The myth of valuation is the idea that you can take this momentary-snapshot stock price and apply it to the entire company — as if the whole market will freeze and let you do so.

Even more important: Stock is speculative — literally. When I buy your company with stock in my company, I’m not handing you money I earned; I’m giving you a piece of the future of my company (the assumption that someday there will be a flow of profits). There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s not remotely the same as giving you cash you can walk away with.

When one company buys another with stock, the entire transaction is performed with hopes and dreams. This aspect of the market is like capitalism’s version of quantum uncertainty: No one actually knows what the acquired company is “worth” until the sell-or-hold choices that people will make play out over time. Some people might get rich; some might get screwed.

Too often, our headlines and stories and discussions of deals closed and fortunes made ignore all this. Maintaining the blur is in the interests of the deal-makers and the fortune-winners. Which is why it persists, and spreads every time the markets go bananas. Then young journalists who have never seen a tech bubble before sally forth, wide-eyed, to gape at the astronomical valuations of itty-bitty startups, without an asterisk in sight.

This distorted understanding of valuation takes slightly different forms depending on the status of the companies involved.

With a publicly traded company, it’s easy to determine a valuation: Just multiply price per share times the total number of outstanding shares, right? But the more shares anyone tries to sell at any one time, the less likely it is that he will be able to get the same price. The more shares you shovel into the market, most of the time, the further the price will drop. (Similarly, if you decide you want to buy a company by buying a majority of its stock, you’ll probably drive the price up.) So stock valuations are elusive moving targets.

For private companies, though, it’s even worse. Basically, the founders/owners and potential investors sit down and agree on any price they like. They look for rationales anywhere and everywhere, from comparable companies and transactions to history to media coverage and rumor to “the back of this envelope looks too empty, let’s make up some numbers to fill it.” If other investors are already in the game, they’re typically involved too; they’re happy if their original investment is now worth more, unhappy if their stake (the percentage ownership of the company their investment originally bought them) is in any way diluted.

There are all sorts of creative ways of cutting this pie. The main thing to know is, it’s entirely up to owners and investors how to approach placing a value on the company. All that private investment transactions (like Series A rounds) tell you is what these people think the company is worth — or what they want you to think it’s worth.

Also: it’s ridiculous to take a small transaction — like, “I just decided to buy 2 percent of this company for $20 million because I think they’re gonna be huge” — and extrapolate to the full valuation of the company: “He just bought 2 percent of us for $20 million, so we’re now a $1 billion company, yay!”

If you can keep persuading lots of people to keep paying $20 million for those 2 percent stakes, and you sell the whole company, then you’re a $1 billion company. Until then, you’re just a company that was able to persuade a person that it might be worth $1 billion someday. During a bubble, many such people are born every minute, but their money tends to disappear quickly, and they vanish from the landscape at the first sign of bust.

If you can keep persuading lots of people to keep paying $20 million for those 2 percent stakes, and you sell the whole company, then you’re a $1 billion company. Until then, you’re just a company that was able to persuade a person that it might be worth $1 billion someday. During a bubble, many such people are born every minute, but their money tends to disappear quickly, and they vanish from the landscape at the first sign of bust.

(Here’s a classic “X is worth Y” fib from the last bubble of the mid-2000s. Note that Digg was ultimately acquired, years later, for a small fraction of the price BusinessWeek floated in 2006.)

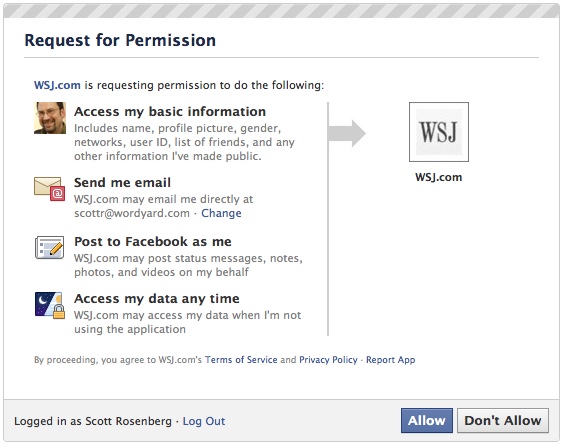

(2) “We will always put our users first”

Many startup founders are passionate about their dedication to their users, in what is really Silicon Valley’s modern twist on the age-old adage that “the customer always comes first.” One of the side-effects of a bubble is that small companies can defer the messy business of extracting cash profits from customers and devote their energy to pampering users. Hooray! That makes life good for everyone for a while.

The trouble arises when founders forget that there is a sharp and usually irreconcilable conflict between “putting the user first” and delivering profits to investors. The best companies find creative ways to delay this reckoning, but no one escapes it. It’s most pronounced in advertising-based industries, where the user isn’t the real paying customer. But even tech outfits that have paying users face painful dilemmas: Software vendors still put cranky licensing schemes on their products, or create awkward tie-ins to try to push new products and services, or block interoperability with competitors even when it would make users’ lives easier. Even hardware makers will pad their bottom lines by putting nasty expiration codes on ink cartridges or charging ridiculous prices for tiny adapters.

But the ultimate bubble delusion is the founder’s pipe-dream that she can sell her company yet still retain control and keep “putting the user first” forever. In the public-company version of this phenomenon, the founder tells the world that nothing will change after the IPO, the company’s mission is just as lofty as ever, its dedication to the user just as fanatical. This certainty lasts as long as the stock price holds up. Legally and practically, however, the company now exists to “deliver value to shareholders,” not to deliver value to users. Any time those goals conflict — and they will — the people in the room arguing the shareholders’ cause will always hold the trump card.

In the private company version, the founder of some just-acquired startup proudly tells the world that, even though he has just sold his company off at a gazillion- dollar valuation, nothing will change, users will benefit, move right along. Listen, for instance, to WhatsApp founder Jan Koum, an advocate of privacy and online-advertising skeptic, as he “sets the record straight” after Facebook acquired his company:

If partnering with Facebook meant that we had to change our values, we wouldn’t have done it. Instead, we are forming a partnership that would allow us to continue operating independently and autonomously. Our fundamental values and beliefs will not change. Our principles will not change. Everything that has made WhatsApp the leader in personal messaging will still be in place. Speculation to the contrary isn’t just baseless and unfounded, it’s irresponsible. It has the effect of scaring people into thinking we’re suddenly collecting all kinds of new data. That’s just not true, and it’s important to us that you know that.

Koum sounds like a fine guy, and I imagine he totally believes these words. But he’s deluding himself and his users by making promises in perpetuity that he can no longer keep. It’s not his company any more. He can say “partnership” as often as he likes; he has still sold his company. Facebook today may honor Koum’s privacy pledges, but who can say what Facebook tomorrow will decide?

This isn’t conspiracy thinking; it’s capitalism 101. Yet it’s remarkable how deeply a bubble-intoxicated industry can fool itself into believing it has transcended such inconvenient facts.

(3) This time, it’s different

If you’re 25 today then you were a college freshman when the global economy collapsed in 2007-8. If you went into tech, you’ve never lived through a full-on bust. Maybe it’s understandable for you to look at today’s welter of IPOs and acquisitions and stock millionaires and think that it’s just the natural order of things.

If you’re much older than that, though, no excuses! You know, as you should, that bubbles aren’t forever. Markets that go up go down, too. (Eventually, they go back up again.) Volatile as the tech economy is, it is also predictably cyclical.

Most recently, our bubbles have coincided with periods — like the late ’90s and the present — when the Federal Reserve kept interest rates low, flooding the markets with cash looking for a return. (Today, also, growing inequality has fattened the “play money” pockets of the very investors who are most likely to take risky bets.)

These bubbles end when there’s a sudden outbreak of sanity and sobriety, or when geopolitical trouble casts a pall on market exuberance. (Both of these happened in quick succession in 2000-2001 to end the original dotcom bubble.) Or a bubble can pop when the gears of the financial system itself jam up, as happened in 2007-8 to squelch the incipient Web 2.0 bubble. My guess is that today’s bubble will pop the moment interest rates begin to head north again — a reckoning that keeps failing to materialize, but must someday arrive.

It might be this year or next, it might be in three years or five, but sooner or later, this bubble will end too. Never mind what you read about the real differences between this bubble and that one in the ’90s. Big tech companies have revenue today! There are billions of users! Investors are smarter! All true. But none of these factors will stop today’s bubble from someday popping. Just watch.