If you look at my life, I’ve never gotten it right the first time. It always takes me twice.

— Steve Jobs, in a 1992 Washington Post interview

I first wrote about Steve Jobs as a digital auteur in January 1999, in a profile for Salon that tried, in the near-term aftermath of Jobs’ return from exile to Apple, to sum up his career thus far:

The most useful way to understand what Jobs does best is to think of him as a personal-computer auteur. In the language of film criticism, an auteur is the person — usually a director — who wields the authority and imagination to place a personal stamp on the collective product that we call a movie. The computer industry used to be full of auteurs — entrepreneurs who put their names on a whole generation of mostly forgotten machines like the Morrow, the Osborne, the Kaypro. But today’s PCs are largely a colorless, look-alike bunch; it’s no coincidence that their ancestors were known as “clones” — knockoffs of IBM’s original PC. In such a market, Steve Jobs may well be the last of the personal-computer auteurs. He’s the only person left in the industry with the clout, the chutzpah and the recklessness to build a computer that has unique personality and quirks.

The Jobs-as-auteur meme has reemerged recently in the aftermath of his retirement as Apple CEO. John Gruber gave a smart talk at MacWorld a while back, introducing the auteur theory as a way of thinking about industrial design, and then Randall Stross contrasted Apple’s auteurial approach with Google’s data-driven philosophy for the New York Times.

(Here is where I must acknowledge that the version of the auteur theory presented in all these analyses, including mine, omits a lot. The theory originally emerged as a way for the artists of the French New Wave, led by Francois Truffaut, to square their enthusiasm for American pop-culture icons like Alfred Hitchcock with their devotion to cinema as an expressive form of art. In other words, it was how French intellectuals justified their love for stuff they were supposed to be rejecting as mass-market crap. So the parallels to the world of Apple are limited. We’re really talking about “the auteur theory as commonly understood and oversimplified.” But I digress.)

Auteurial design can lead you to take creative risks and make stunning breakthroughs. It can also lead to self-indulgent train wrecks that squander reputations and cash. Jobs has certainly had his share of both these extremes. They both follow from the same trait: the auteur’s certainty that he’s right and willingness (as Gruber notes) to act on that certainty.

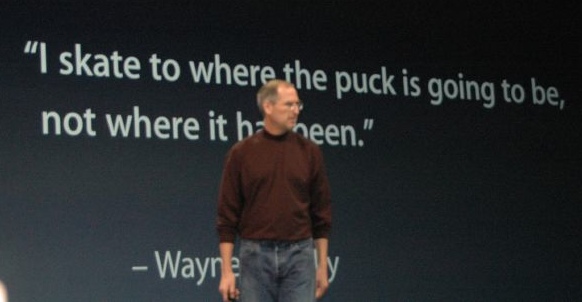

Hubris or inspiration? Either way, this kind of auteur disdains market research. “It isn’t the consumers’ job to know what they want,” Jobs likes to say. Hah hah. Right. Only that, the democratic heart of our culture tells us with every beat, is precisely the consumer’s job. To embrace Jobs’ quip as a serious insight is to say that markets themselves don’t and can’t work — that democracy is impossible and capitalism one colossal fraud. (And while that’s an intriguing argument in its own right, I don’t think it’s what Jobs meant.)

I have to assume what Jobs really means here is that, while most of us know what we want when we’re operating on known territory, there are corners that we can’t always see around — particularly in a tumultuous industry like computing. Jobs has cultivated that round-the-corner periscopic vantage for his entire career. He’s really good at it. And so sometimes he knows what we want before we do.

I find nothing but delight in this. I take considerable pleasure in the Apple products I use. Still, it must be said: “I know best” is a lousy way to run a business (or a family, or a government). It broadcasts arrogance and courts disaster. It plugs into the same cult-of-the-lone-hero-artist mindset that Apple’s ad campaigns have celebrated. It reeks of Randian ressentiment and adolescent contempt for the little people.

Jobs’ approach, in Jobs’ hands, overcame this creepiness by sheer dint of taste and smarts. There isn’t anyone else in Apple’s industry or any other who is remotely likely to be able to pull it off. If what Jobs’ successors and competitors take away from all this is that “we know best” can be an acceptable business strategy, they will be in big trouble.

But there’s a different and more useful lesson to draw from the Jobs saga.

The salient fact about the arc of Jobs’ career is that his second bite at Apple was far more satisfying than his first. Jobs’ is a story that resoundingly contradicts Fitzgerald’s dictum about the absence of second acts in American life. In a notoriously youth-oriented industry, he founded a company as a kid, got kicked out, and returned in his 40s to lead it to previously unimaginable success. So the really interesting question about Jobs is not “How does he do it?” but rather, “How did he do it differently the second time around?”

By most accounts, Jobs is no less “brutal and unforgiving” a manager today than he was as a young man. His does not seem to be a story of age mellowing youth. But somehow, Jobs II has succeeded in a way Jobs I never did at building Apple into a stable institution.

I’m not privy to Apple-insider scuttlebutt and all I really have are some hunches as to why this might be. My best guess is that Jobs figured out how to share responsibility and authority effectively with an inner circle of key managers. Adam Lashinsky’s recent study of Apple’s management described a group of “top 100” employees whom Jobs invites to an annual think-a-thon retreat. Jobs famously retained “final cut” authority on every single product. But he seems to have made enough room for his key lieutenants that they feel, and behave, like a team. Somehow, on some level, they must feel that Apple’s success is not only Jobs’ but theirs, too.

Can this team extend Jobs’ winning streak with jaw-droppingly exciting new products long after Jobs himself is no longer calling the shots? And can an executive team that always seemed like a model of harmony avoid the power struggles that often follow a strong leader’s departure? For now, Jobs’ role as Apple chairman is going to delay these reckonings. But we’re going to find out, sooner or later. (And I hope Jobs’ health allows it to be way later!)

If Apple post-Jobs can perform on the same level as Apple-led-by-Jobs, then we will have to revise the Steve Jobs story yet again. Because it will no longer make sense to argue over whether his greatest achievement was the Apple II or the original Mac or Pixar or the iPod or the iPhone or the iPad. It will be clear that his most important legacy is not a product but an institution: Apple itself.