[This article, which is a collaboration between me and Mark Follman, originally appeared on the Atlantic’s website. Since then it has been the subject of a MediaBugs error report filed by Frank Lindh. Yes, at MediaBugs, not only do we eat our own dogfood, we find it tasty!]

It is hard to describe the interview that took place on KQED’s Forum show on May 25, 2011, as anything other than a train wreck.

It is hard to describe the interview that took place on KQED’s Forum show on May 25, 2011, as anything other than a train wreck.

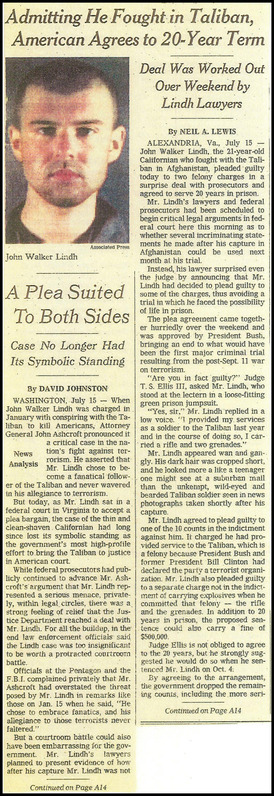

Osama bin Laden was dead, and Frank Lindh — father of John Walker Lindh, the “American Taliban” — had been invited on to discuss a New York Times op-ed piece he’d just published about his son’s 20-year prison sentence. The moment host Dave Iverson completed his introduction about the politically and emotionally charged case, Lindh cut in: “Can I add a really important correction to what you just said?”

Iverson had just described John Walker Lindh’s 2002 guilty plea as “one count of providing services to a terrorist organization.” That, Frank Lindh said, was simply wrong.

Yes, his son had pled guilty to providing services to the Taliban, in whose army he had enlisted. Doing so was a crime because the Taliban government was under U.S. economic sanctions for harboring Al Qaeda. But the Taliban was not (and has never been) classified by the U.S. government as a terrorist organization itself.

This distinction might seem picayune. But it cut to the heart of the disagreement between Americans who have viewed John Walker Lindh as a traitor and a terrorist and those, like his father, who believe he was a fervent Muslim who never intended to take up arms against his own country.

That morning, the clash over this one fact set host and guest on a collision course for the remainder of the 30-minute interview. The next day, KQED ran a half-hour Forum segment apologizing for the mess and picking over its own mistakes.

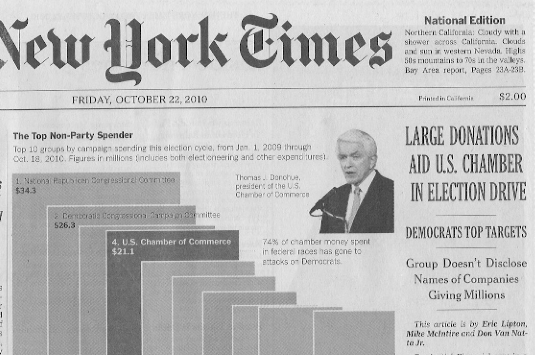

KQED’s on-air fiasco didn’t happen randomly or spontaneously. The collision was set in motion nine years before by 14 erroneous words in the New York Times.

This is the story of how that error was made, why it mattered, why it hasn’t been properly corrected to this day — and what lessons it offers about how newsroom traditions of verification and correction must evolve in the digital age.