Sharing links keeps evolving. Today your Facebook feed rules, but it’s not going to be that way forever (ask any teenager). Blogs began largely as a way to share links, and though the form evolved beyond that, it never resolved the tension between “linkblogging” and diary-keeping or opinionating.

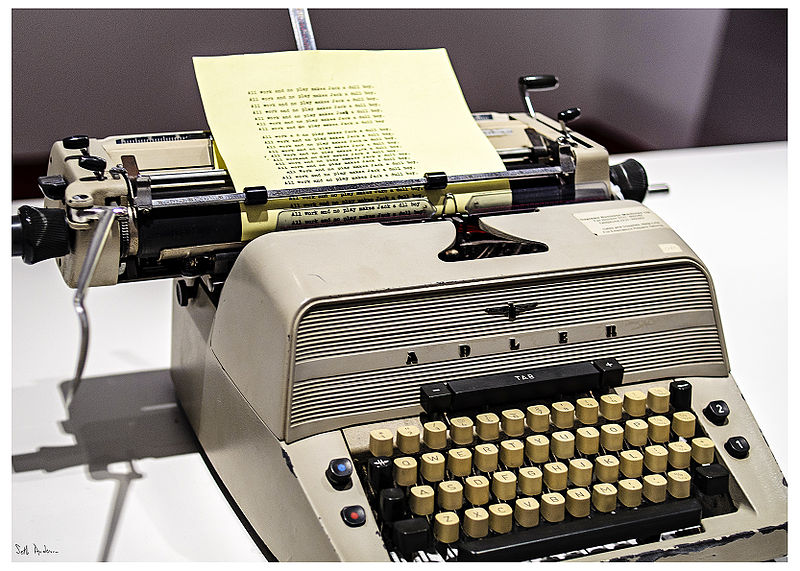

What’s the best way to share links in 2016? Twitter, mostly, is what I’ve been using, and it’s fine, it works, but there’s a certain dust-in-the-wind quality to it, an even-deeper-than-digitally-normal futility. Links in tweets are atoms in the void; there’s little-to-nothing you can do with them to organize them as data. Also, if you like to share quotes or excerpts, you run out of space fast — and I will not do the “post an image of a block of text” thing, on principle. (It took years to win the war in web design against text-in-images, and I’m not going back.)

The other popular and effective link-sharing strategy today is — hilariously, this being 2016 — email. And it works pretty well, too! Particularly for publishers and intelligent curators. But many email-newsletter services now hide the real URL of a link behind some sort of tracking code. That’s great in terms of them knowing where you go, lousy in terms of you knowing where you’re going. The best purveyors of email links either don’t do this at all, or make a point of IDing the link fully within the body of their message. Too often, though, an email link is a blind link.

How else do links travel today? Within Slack, for sure. On Reddit and Hacker News and similar forums, still. And on some interesting new channels like This., where you are encouraged to share only one link a day and make it count.

For years now, I’ve been collecting links on the ever-mutating theme of authenticity in the digital age. For a while when I was posting daily here I included a link roundup once a week. But I wasn’t thrilled with that format and stopped.

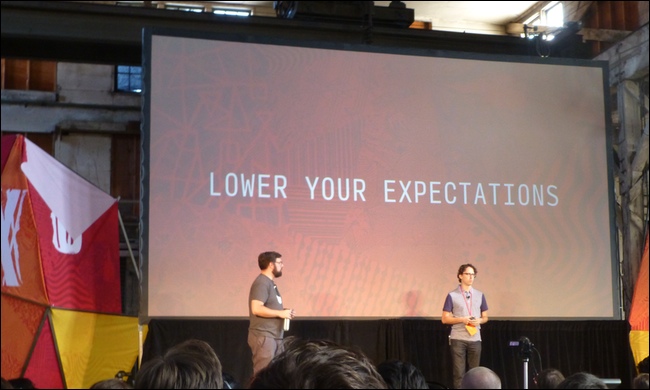

As an experiment at the start of this new year, I’m going to play around with a more promiscuous link-sharing strategy. Here’s the plan right now:

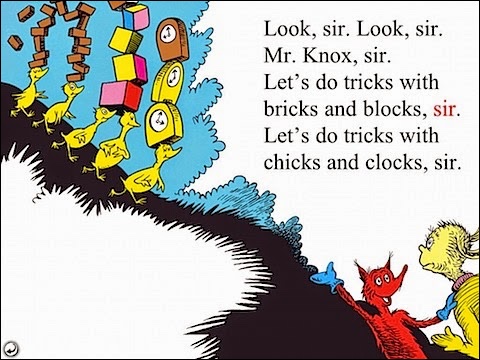

- Roughly one link each day

- The topic is digital authenticity, broadly defined

- A mix of new finds and oldies

- Quoted, documented, credited, of course

- Presented in a variety of venues

- Freely experimenting with different formats and channels

At the start, I plan to post here as home base. I’ll tweet the link, too. I’ll put it on Facebook. I’ll put it on This. And I’ll email a digest once a week. I’ll add to and subtract from this distribution approach as feels right. And I’ll try to report back with anything I learn from the process.

![The green monster [photo by Scott Beale]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/metal-press-scott-beale.jpg)

![Belmont Goats [photo by John Biehler]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/xoxogoats.jpg)

![[Duncan Rawlinson]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/independencemyth.jpg)

![Anita Sarkeesian [photo by Duncan Rawlinson]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/sarkeesian.jpg)