“Don’t fly your drones over the goat field!”

Not your everyday conference-behavior tip, but Portland’s XOXO Festival is anything but everyday.

The festival concatenates bold tech dreams and warm organic substance into a rare alchemy, like a green flash of Now. The 2014 edition took place in a cavernous, dilapidated former iron foundry. Days before the event, its exterior was covered with bright geometric splashes of red, yellow, orange, and black. Inside, a giant hulk of a hydraulic press loomed over us — a ghost-machine of makers past.With their exhortation, the event’s two impresarios, Andy Baio and Andy McMillan, were telling us to take care that our high-tech exuberance didn’t cause any unnecessary harm to furry animals. But drones? Goats?

Last year, the festival had hosted a talk by Chris Anderson about how drones could transform agriculture by giving farmers real-time info about the state of their fields. Later he led live drone demos over the gigantic empty lot next door to the event space. Only it turned out that the lot wasn’t empty; an urban-farming showcase, it was home to a small goat herd.

Now, these goats are not Luddites — they’re on Twitter, after all. But the flying bots freaked them out. As the kissy-huggy festival name implies and its three-year tradition has embodied, XOXO is all about kindness and consideration. So this year, yes, drones were on hand for the festival once more, and some of them got some awesome aerial shots of the venue’s crazy paint job. But instead of a Great War between buzzing quadcopters and bleating quadrupeds, we had caprine-drone detente.And it was nice! Little goats, led on leashes like pups, visited the edge of the festival’s food-truck lot, eying a dazzling array of artisanal lunch options — wood-fired pizza, gourmet PBJ, a Korean BBQ named Kim Jong Grillin’. Attendees, in turn, made the two-block trek to the goat field to pet and gawk.

The sorts of conflicts that XOXO’s impassioned speakers addressed — thorny, achy collisions of ambition and reality, creativity and commerce — are rarely so simply resolved. That this gathering dedicated to independent makers of tech and art acknowledges such conflicts at all — that here they are explored and deplored, celebrated and satirized — sets XOXO apart from the raft of tech-biz conclaves that sell you ways to monetize your dreams. People keep flocking back to the thing because it’s like a food truck for the creative soul: It comes around infrequently; it sells out all the time; and the lines can be daunting. But man, you’ll remember that meal.

Each year the XOXO Festival is well-documented by attendees (check out Kevin Marks’ excellent tweet-notes from both days of talks this year), and you could do a lot worse than hunker down with the official videos from the event once they’re posted. I can’t recall another gathering where I got something out of every single speaker’s presentation — 20-25 minute talks, no panels, no Q&A, just the distilled thoughts of smart people who’ve brought their best because they know they’re talking to their peers.

At the first XOXO two years ago, Kickstarter (which Baio helped build) was new, the world was dusting itself off from a dreadful recession, and the message was: Do what you love and the Internet will provide. It was stirring, and a lot of people said that it changed their lives.

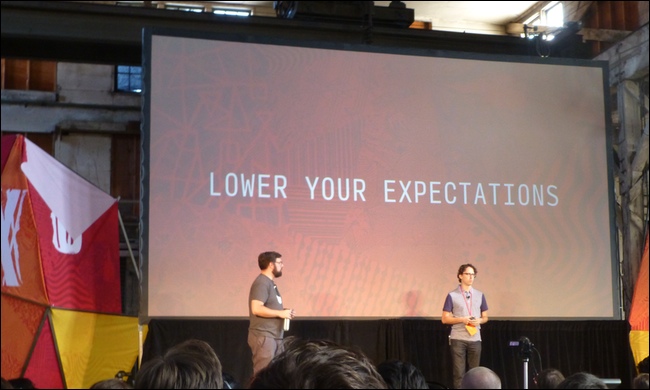

This time, the mood was more sober, and the theme, as Baio articulated it, was less “You can do it!” than “You are not alone.” Over the summer, a young developer/artist and festival regular named Chloe Weil had killed herself. (Baio and MacMillan dedicated the event to her.) Speaker after speaker described wrestling with depression, or bankruptcy, or loneliness and doubt.

Sure, creative highs have always come with real-world lows. Lifehacker and Thinkup founder Gina Trapani offered solace to the struggling: “Someday, somehow your worst moments are going to feed your best work.” But of course success is never guaranteed — and even when you find it, don’t relax too fast.

Hank Green, the geekier half of the VlogBrothers, declared, “Moments of extreme success are depression triggers for me. Three days later I can’t get out of bed. WHAT THE FUCK?” The audience gave a round of “us, too” cheers.

Here are some themes I found coalescing in the XOXO ferment.

Personal obsessions power sustained work

When Kevin Kelly’s kids went off to college he sent them each off with a crate of tools, but he could only fit so much in the box and he wanted to give them more, so he made the Cool Tools book, a kind of latter-day Whole Earth Catalog that he self-published. “I only needed three copies,” he said, but he sold 42,000. “The rest was just gravy.”

Trapani told how she came to found Lifehacker, a site that’s all about “clever tricks to save you time, efficiency and productivity.” She’d experienced 9/11 from a Lower Manhattan office and become obsessed with the feeling that “time was running out” and she was wasting it. An original motto for the site — unused — was: “Because someday you’re going to die.”

Daring Fireball founder John Gruber started covering Apple in 2002, when the company was still an ailing underdog, not because he anticipated it would become today’s product-perfecting, profit-spouting juggernaut, but because he was obsessed with the company and needed to write about it. It wasn’t a bet; it was an infatuation.

Writer/developer Paul Ford is building a tool for collecting, annotating and crossreferencing texts called Unscroll.com. Why? Well, he’s worked on projects like this for a long time — including a visionary rethinking of the Harper’s Magazine website a decade ago that turned the archive into a time machine. But today, he says, he’s driven, at least in part, by a wish to preserve the work of his friend Leslie Harpold, a pioneering blogger who died in 2006.

Failure and success aren’t opposites — they’re more like phases

Rachel Binx makes cool stuff — including jewelry shaped by personal location graphs and greeting cards embodying animated GIFs via lenticular printing. But her attempt to launch a conference failed and her income has been spotty. The message of her bracingly honest talk: Don’t assume that having and executing great ideas leaves you immune from cash-flow woes. Still, there’s at least one bright spot: “Now,” she said, “I can write a Medium post about failure!”

Justin Hall, who started sharing his life online when the Web was young, promised to reveal all the secret moves he used to bring his site traffic from 27,000 daily visitors in 1995 to, um, 270 today. The years have tempered, but not dissolved, his youthful belief that “strangers + honesty = empathy.”

Joseph Fink, a creator of the overnight-sensation podcast Welcome to Night Vale, described how success changed the circumstances of his work. On the one hand: He could leave behind a day-job trying to sign people up for a wind-energy service. On the other hand: “Success turned my friends into my coworkers,” he said. “The relationship I had with them before is gone.” Also: “There are now thousands and thousands of people who care about what we do, and that’s genuinely terrifying.”

No one captured this notion of success and failure as two sides of one coin more cleverly than Darius Kazemi — whose domain name and twitter handle, “tiny subversions,” characterizes the kind of work he does. “HOW I WON THE LOTTERY,” his XOXO talk, is a perfect little satire of go-for-it tech-business talks that concludes with three bullet points:

- I didn’t know what I was doing

- I kept buying lottery tickets

- I built a community

A summary won’t do Kazemi justice; watch the video when it’s posted.

Kevin Kelly urged us to think about more diverse definitions of success than the venture-capital-driven, scale-up-fast Internet startup economy offers. Internet startups are like pigeons, he said — the system produces them in abundance so that a few can survive. But we also want, and need, birds of paradise. Similarly, products with broad but shallow appeal prosper in the present: the hit song, the big movie, the bestseller. But a hundred years later, all these hits are gone. Stuff that gets loved passionately by a smaller following is different: It’s more likely to last.

Persistence is its own reward

Jonathan Mann, the song-a-day guy, has produced more than 2000 songs on YouTube over the last half-decade. He says that maybe 10 percent of them are good, 20 percent bad, the rest “okay.” The “good” shows up unpredictably: “A lot of the days that my favorite songs come out, it feels like I have nothing, and then it appears.”

Sometimes creativity is the result of such spontaneity — as with the punky dashed-off process that Thermals singer Hutch Harris used to write and record the raw “No Culture Icons,” which he described at XOXO to Song Exploder‘s Hrishikesh Hirway. Other times, creativity can take forever. The stop-motion video artist known as PES said he’ll spend weeks painstakingly rearranging everyday objects, frame by frame, to produce a single one- to two-minute video — like “Game Over,” a sort of meatspace cover version of classic videogames using, for instance, a little round pizza as Pac-Man and bugs as Space Invaders.

That’s crazy! Still, if that’s what you love doing, why not? Green says that as he and his brother got their YouTube show up and running, he discovered that, for all his ambition and devotion to teaching people about science, editing video is what really rings his bell. If you’re doing something you love, then the work isn’t a slog toward some distant goal; it is its own reward.

Which is why XOXO was full of people saying that they weren’t looking for exits — they just wanted to keep doing what they were doing forever. The Unscroll.com project, Ford said, is what he wants to be working on for the next 20 years. Gruber declared: “I’m going to write Daring Fireball until I fucking die.”

Independence is a myth

The XOXO crowd cherishes independence in the way that creative types do. Who wants to have funders/suits/studio execs/producers telling you what to make or how to make it?

Erin McKean, the lexicographer turned entrepreneur behind Wordnik, reminded us that no one can create alone, in a vacuum. “Unless you’re independently wealthy and incredibly reclusive, every maker is dependent on somebody.” She’s right. More accurately, “independence” here means having the autonomy to choose exactly who or what you’re going to depend on to get your work done. Will you be in the thrall of investors? Fans? Collaborators? Partners? A day job at a big company?

Understood this way, crowdfunding is less a lucky ticket out of bondage than another option with its own tradeoffs. Which means that it’s not the solution to every problem. That may be one reason that venture capital has become somewhat less of a dirty word in these precincts. Even as Jen Bekman told a familiar but sadly common tale of the Death by VC that befell her art-for-the-people site 20×200 (she has since resurrected it), and Justin Hall recounted the flameout of his Gamelayers startup, other speakers described a saner, scaled-down approach to VC underwriting that might make sense for the indie world.

Trapani’s ThinkUp, which helps users analyze their activity on social networks, is one; Ethan Diamond’s Bandcamp, which helps musicians connect directly with their fans and is now funneling $3 million a month into their pockets, is another. (Diamond said the amount of investment Bandcamp accepted was the kind of money you’d find “stuck between the seat covers of the VC’s Tesla.” The company set up office at a local public library for its first four years.)

Probably the most moving revelation of interdependence came from Golan Levin and Pablo Garcia, the founders of NeoLucida, a crowdfunded project to mass-produce a modern camera lucida device — a “prism on a stick” that projects images onto flat surfaces so you can draw them. Artist-provocateurs who used their Kickstarter email updates to deliver art-history lectures, Levin and Garcia wanted to fathom the nature of the Chinese factory that produced their devices, so they paid a visit, met the workers, and talked to them about their stories.

“What we learned in China is that all of our stuff is hand-made, even if it looks like it isn’t,” Garcia said. “There are handprints on everything.”

“You can weaponize nice”

One of the foundational principles of the XOXO worldview is that you don’t have to be an asshole to be an artist; great things can be created by nice people. McKean, who introduced herself as “the female founder of a Silicon Valley VC-backed startup that has nothing to do with fashion,” talked about being told she was “too nice,” experimenting with “bitch-face” but deciding that it just wasn’t her. “I reached back into my ancestral knowledge and realized: you can weaponize nice” — meaning, you can have the ability to “tell someone to go to hell and they’ll enjoy the trip.”

XOXO runneth over with nice. And nice can certainly make for an enjoyable, edifying weekend. If you want to change the world, however, nice is probably not enough. But “weaponized” nice — niceness organized and creative energy directed toward action? Maybe there’s your Archimedes’ lever.

You could glimpse what that might look like in the talk by Anita Sarkeesian, the feminist videogame critic whose incisive work has attracted a swarm of harassers and abuse. At XOXO Sarkeesian pointed her analytical scalpel at the dishonest methodology of her critics — no, critics isn’t the right word for them, because there seems to be no actual criticism in their response, just anger, misogyny, and lies. Sarkeesian has every right to be angry back at them, but she keeps her cool and lets the abusive comments and impersonations speak for themselves. I wouldn’t call her “nice” — more like professional and brave and determined to do her work. But this feels close to what McKean was talking about.

I suppose it was inevitable that Sarkeesian-haters and “men’s-rights” types would turn up on Twitter at the #xoxofest hashtag, claiming to be present at the conference and misquoting her talk. One guy even showed up in person, handing out leaflets and attempting to engage with festivalgoers at the goat field. Cruelty to goats!

No amount of nice is going to make a difference in this sort of conflict. You are unlikely to win a reasonable argument with a fanatic, and you probably won’t even be able to have one.

But the handful of trolls on Reddit or 4chan, seething in their ressentiment, are a nasty sideshow to a far more important process unfolding — the one where we come to accept that the intersection of art and tech is a culturally important place. A place worth defending from idiots. A place where we ought to listen when smart people tell us who’s being left out and what voices need to be heard. A place that we can renovate and change once we understand what needs to be done.

You don’t need a drone to see that. Then again, a drone might get you a better picture.

Post Revisions:

- September 17, 2014 @ 20:01:06 [Current Revision] by Scott Rosenberg

- September 17, 2014 @ 20:01:06 by Scott Rosenberg

- September 17, 2014 @ 16:34:28 by Scott Rosenberg

![The green monster [photo by Scott Beale]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/metal-press-scott-beale.jpg)

![Belmont Goats [photo by John Biehler]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/xoxogoats.jpg)

![[Duncan Rawlinson]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/independencemyth.jpg)

![Anita Sarkeesian [photo by Duncan Rawlinson]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/sarkeesian.jpg)