My first chat-enabled workplace was the Salon newsroom circa 2000 AD, when we were expanding like crazy and covering the chaos of the Florida Bush v. Gore election recount. Our dotcom-bubble-inflated staff, spread between SF and NY and DC, needed to stay in touch by the hour, sometimes by the minute. AIM was our channel. Though I might not have wanted to rely on AOL for any kind of secure communications, it was free and worked fine. And of course it had emoticons.

AIM’s day came and went, but the utility of connecting remote work locations with chat has become an essential service — knitting desktop and mobile device, home and office, day and night into one seamless Now of work. Skype has been a popular choice for many small and medium-sized organizations, but its owners at Microsoft neglected it over the years, and its notifications and cross-device tracking of “new since last read” grew more erratic. Recently, the startup Slack has taken off and filled this niche for a growing number of workplaces. Spiffily designed, customizable, interoperable, searchable, and efficient, it’s like chat on speed and with its own brain.

Chat is great! You get to share office camaraderie, raillery, and bad puns even when you work remotely. But it raises a whole new slew of challenges in our lives. Deployed humanely and sensibly, it can provide workers with more freedom and flexibility and employers with better results and lower costs. But too often companies and organizations adopt it as a technology of control.

On the more benign end of the spectrum, the chat system becomes a theater of availability where employees perform their presence and enthusiasm to impress or placate their managers. At the worse end, the whole thing can very quickly turn into a nightmare of surveillance and time-tracking overkill — digital Taylorism.

I recently talked with an old friend and former colleague who felt stalked by a startup-CEO boss who was using Slack to check up on employees and make sure they were available 24/7 to meet the company’s needs. Given the promise in Slack’s name of providing your worklife with a tension-reducing buffer, this was ironic. Of course, it’s also an issue with startup culture that transcends the use of particular tools. A boss who is determined to rub out the boundary between work and personal time is going to grab anything handy to make that happen. But tools like Slack can certainly streamline the process.

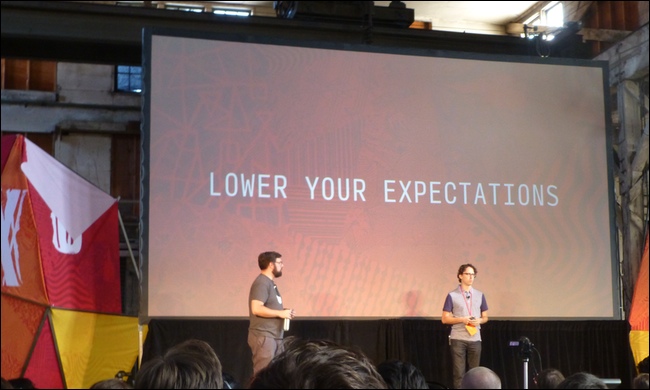

I think a lot of us love the flexibility and fun that chat systems provide and wouldn’t want to give it up. But we also need some way to keep work from invading every minute of every day. The simplest and most effective way for this to happen is for enlightened managers to make clear to teams exactly what sort of responsiveness and attentiveness they expect from employees using chat — so that the employees aren’t in the lousy position of trying to guess what the norm is, or outdo one another.

When I started my career at a newspaper, there were very clear understandings between management and the Newspaper Guild as to who owned which hours of my day. Every week I filled out a timecard — yes, an actual piece of cardstock — reporting my hours, and every week I basically made it up. There was no way I ever worked a normal 8-hour day. As a theater critic seeing shows, writing at night, and doing background research and reading during the day, I wasn’t in a position to draw clear lines between work and pleasure. It was all OK for me; I didn’t mind because I loved it all.

In that era, the expectations were clearly laid out but meaningless. Today, a lot of “knowledge workers” find themselves in a much tougher position: no clear expectations from their leadership and torn between a desire to do a great job and the need to preserve some time for family, personal life, all the Stuff that Isn’t Work.

We need to get much better at this — to find ways to make great tools like Slack increase, not diminish, the sum total of workplace sanity.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=slfFJXVAepE

![The green monster [photo by Scott Beale]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/metal-press-scott-beale.jpg)

![Belmont Goats [photo by John Biehler]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/xoxogoats.jpg)

![[Duncan Rawlinson]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/independencemyth.jpg)

![Anita Sarkeesian [photo by Duncan Rawlinson]](http://www.wordyard.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/sarkeesian.jpg)