I don’t think I’ve ever taken Technorati’s annual blogger survey before, but the company’s annual reports have usually been a useful source of information, so when I got an email inviting me to respond I took a few minutes to do so.

I began to think something was off when I saw this question:

WordPress’s hosted service at WordPress.com, which has gazillions of users, is free. I host my own blog using the WordPress.org open-source version. I do pay an ISP for server space, so maybe that’s considered “a paid third-party hosting service,” but boy is this confusing! Meanwhile, it’s 2010 — how many people handcode their own HTML? Isn’t it, like, statistically insignificant?

On to the next head-scratcher:

Um, my Twitter account is linked to my blog. Like a horde of other bloggers I use a widget to display my tweets on my blog. But like so many other bloggers I don’t feed my posts automatically into Twitter, because Twitter works better when you actually speak as a person. So there’s no accurate way to answer this question.

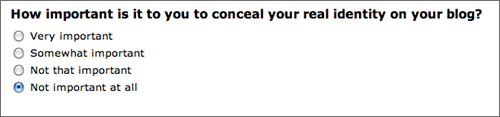

Then there was this:

The question’s wording presupposes that the respondent is blogging anonymously, which is just plain weird, since most bloggers identify themselves.

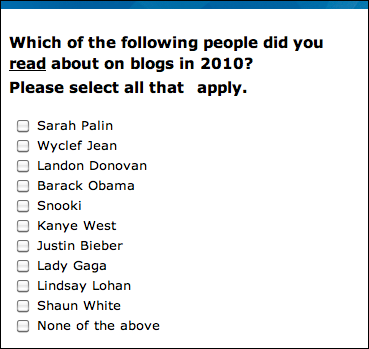

This question began to suggest where Technorati’s head was at.

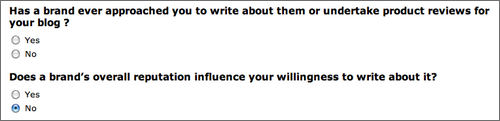

It turned out that the survey was heavily focused on the role of “brands” in blogging, which is usually a signal that somebody somewhere has dollar signs in their eyes.

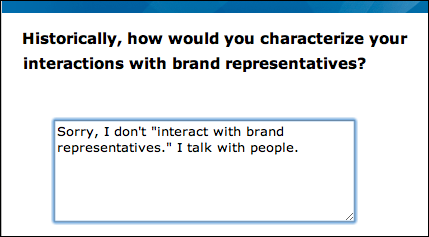

“Has a brand ever approached you…?” How exactly would a brand do that? Have brands grown mouths and legs?

I’m usually courteous but I guess I snapped.