I. Turn around and hate it

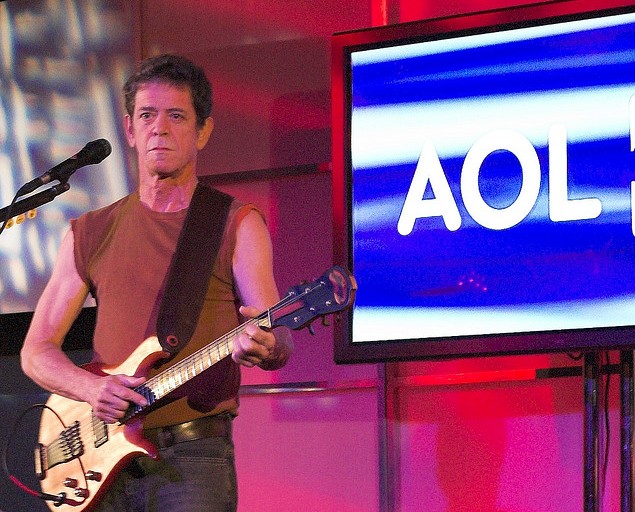

Lou Reed cast a stony stare over a hotel ballroom packed with entrepreneurs, venture capitalists and geeks. It was November 8, 2006, the peak of the last Web bubble — remember? the littler one? the one between the monster bubble that ended in a big mess in 2000 and the bubble we’re in now that will end in another big mess one of these days?

That one, right: the bubble we called “Web 2.0.” That was also the name of the conference that Lou Reed was very visibly getting pissed off at — because, as he stood there and played his guitar and sang his songs, the geeks and VCs and founders weren’t listening. They were talking.

Reed was not known for suffering fools or turning the other cheek; he was famously prickly. (One live track from 1978 captures a rant he directed from the stage at a critic: “What does Robert Christgau do in bed? I mean, is he a toe fucker?”) So maybe the whole idea of having him serve as the after-dinner entertainment for a Web-industry conference hadn’t been so bright. But here we were!

Reed stopped playing. An AOL logo haloed his leathery face. While one of his two accompanying bassists vamped, he began barking at the crowd.

“You got 20 minutes. You wanna talk through it, you can talk through it. Or I can turn the sound up and hurt you.”

This suggestion from the man who wrote “Vicious” elicited a wan cheer.

“You want it louder? Frank, turn it up!”

Turn it up Frank did, to ear-punishing levels. That pretty much ruled out talking valuations and pitch decks and APIs with the person next to you. The whole event now felt like an encounter between hostile forces: disruptive market capitalism versus disruptive confrontational art.

Web 2.0 was supposed to be all about user participation and network value. It was idealistic about building open platforms to empower individuals and crowds — while remaining a little coy, if not outright cynical, about who was going to reap the profits resulting from what those individuals and crowds actually did on those platforms.

Maybe it was only to be expected that the folks who had championed peer-to-peer interactivity and comments and “user-generated content” would not sit back and just passively consume the performance in front of them. Or maybe they were just being rude. Either way, it did not look like it was going to end happily.

If you were sitting near the front of the ballroom, as I was that night, this was the moment when you became aware of some kind of commotion toward the back. Had fisticuffs broken out? Was there a medical emergency? No, it was Tim O’Reilly — the publisher and tech pundit who’d coined the term “Web 2.0” and cofounded the eponymous conference — doing a herky-jerky dance, all by himself, wobbling down the aisle like an off-balance top.

It was brave and a little nuts, and for quite some time O’Reilly was on his own. But it gave us something to look at besides Angry Lou’s glare, and it defused some of the tension in the room. Finally, someone else stood up and joined O’Reilly; then a handful of people more. When Reed broke out the chords to one of his best-known songs, the room burst to life. People stood up, dancing or clapping. With relief, we eased into our role as “the audience.”

That song was “Sweet Jane.”

II. Other people have to work

I first heard “Sweet Jane” in 1970, age 11, sitting on the floor of my older brother’s room in Jamaica, Queens. I had no idea what the words were or what the song was about, and I didn’t care. All that mattered was that riff. Just three syncopated chords! Well, four, really — as Reed will explain for you, and Elvis Costello, here:

Also: a pushy bassline that elbowed its way on either side. A mid-tempo beat like a gleaming railroad track. And Reed’s baritone, deployed in some crazy mashup of Beat recital, Wagnerian sprechgesang, and rap, stepping in and out of the way, spitting out words as if between cigarette puffs. It all worked, just as “Louie Louie” had, and “Wild Thing,” and “Twist and Shout,” and all the other hook-driven songs that most people had stopped listening to by 1970.

Don’t know it? Take a listen:

So I listened, too, over and over — not yet aware that Reed’s group, the Velvet Underground, had started out as Andy Warhol’s house band and explored shadowy frontiers of sex, drugs, and noise for years with no commercial success and had already broken up when Loaded, the album featuring “Sweet Jane,” came out.

It was decades later before I actually paid attention to the song’s words. They had gone through many changes before Reed settled on the version recorded on Loaded, and they remain cryptic in places. But it’s clear what “Sweet Jane” is all about: A rocker glimpses a couple of friends. Thinks about their mundane lives. Weighs taking the cynical view, and rejects it — concluding that no, beauty is not a scam, goodness is not a lie, and both can be found in the stuff of everyday life.

The song is aggressively untrendy, anti-hip, playing against all the fashions of 1970. It rejects both lazy downtown nihilism and counterculture protest. It offers a little nostalgia for old-time “rules of verse,” classic cars — even classical music. It embraces the working life of banker Jack and clerk Jane, and winks at them with a playful touch of cross-dressing kink. (“Jack’s in his corset, Jane is in her vest” — although, for years, I thought Reed was saying “Jack’s in his car,” and to this day so do many of the lyrics sites.) But the song only nods to the demimonde; it’s more the stay-at-home type.

“Sweet Jane” moves, verse by verse, from standing on a street corner to sitting down by the fire to pondering the meaning of life. Near the end it takes full-throated flight with this emphatic credo:

Some people, they like to go out dancing

Other people, they have to work

And there’s even some evil mothers

They’re gonna tell you that everything is just dirtThat women never really faint

And that villains always blink their eyes

And that children are the only ones who blush

And that life is just to dieBut anyone who ever had a heart

They wouldn’t turn around and break it

And anyone who ever played a part

They wouldn’t turn around and hate it

It’s easy to get distracted by the curled lip, the black leather, the shades, and the swagger — all part of the “Lou Reed” act, and all intentionally misdirecting your gaze. But in “Sweet Jane” Reed made very clear that, if you could for just one second stop his guitar hook from looping in your brain and listen to his words, he was always, at heart, an idealist.

III. I’m in a rock and roll band

I learned to play the guitar so I could play “Sweet Jane.” There were only three chords. (Oh, right, four.) It couldn’t be that hard, and indeed it wasn’t.

But for the longest time, playing any chords was, for me, a foreign country. No one I knew as a teenager had a guitar — the kids I ran with played D&D, not Dylan. It wasn’t until my mid-20s, in the ’80s, that I figured out this was something I could actually do. I went with a kind and knowledgeable friend to a little shop on Mass Ave. in Cambridge, bought a cheap acoustic, crossed the street with it to my apartment, and realized just how easy it was to put D, A, and G together. I sounded awful for a long time. But the guitar is a forgiving instrument, and I could coax just enough joy from it to keep me going.

“Sweet Jane” was a starter drug, and since then I’ve learned to play other favorite songs. (“Waterloo Sunset.” “Pinball Wizard.” “Welcome to the Working Week.” Half the Mountain Goats catalog. And so on.) I remain a lousy guitarist, a lefty-playing-righty with a vigorous strum and not much else. But I’ve learned what musicians have always known: Playing a song changes your understanding of it. Playing music changes how you listen to it. Doing changes knowing.

Anyone who wants to learn “Sweet Jane” today can look it up on YouTube and get schooled by gawky kids and middle-aged instructional-video peddlers and all sorts of other people who have chosen to say, “I will show you how I do this.” You can listen to and compare a fat catalog of live performances by Reed and covers by others. (You may visit the “Sweet Jane” Museum I have assembled here, if you like.) The Web has, among many other achievements, allowed us all to produce and share the instruction manuals to our DIY dreams. Pickers and strummers everywhere who have posted your clumsy, loving, earnest videos: I thank you and salute you!

Yet this eruption of knowledge-sharing is usually understood, and often dismissed, as an essentially marginal phenomenon. Let the passionate indulge their pastimes, but we’re basically talking hobbies here, right? Consequential things involve cash. They are metricized and monetized.

The same logic was used for years to belittle the rise of blogging, at a time when it was though to be a pursuit fit only for the pajama-clad. “That’s cute,” said the insiders and the media-savvy. “But it is of no consequence.”

Yet the consequences were real and substantial. Large numbers of people discovered a new opportunity to control a media platform and project a personal voice into the network. Before you knew it, blogs were being metricized and monetized. Then Facebook and Twitter came along and made it far easier for people to post, share, and kibitz without committing to a regular publishing project. These platforms moved quickly toward metrics and monetization, too.

Whether we are teaching guitar or ranting about politics or blogging about our lives, the trend here moves inevitably from small numbers to large, from private pursuit to professional endeavor, and from labor-of-love to cashing in or out. There has been no shortage of analyses and tools to help us understand the numbers and the money at each stage of this evolution. And we have held lengthy, valuable, and — yes — repetitive arguments about the impact of these changes on the collective mediasphere. Do they enrich or impoverish public discourse? Is there more variety or less? More choice or less?

But we haven’t kept as close an eye on how each turn of the digital-era wheel affects us, subjectively, as individuals. That is, we have looked at the numbers and the economics and the technology, but not so much at how the experiences we’re having in our newly-constructed digital environments are shaping us. It’s only recently that we have begun to ask whether Facebook makes us happy (or unhappy), Twitter keeps us connected (or distracted), our devices serve us or the companies that supply them.

One thing we can say with some certainty is that, for the first time in the still-short span of human history, the experience of creating media for a potentially large public is available to a multitude. A good portion of the population has switched roles from “audience” to — speaker, creator, participant, contributor, we don’t even have the proper word yet.

Forget whether this is “good” or “bad”; just dwell with me for a moment on its novelty.

Millions of people today have the chance to feel what it’s like to make media — to create texts or images or recordings or videos to be consumed by other people they may or may not know. Whether they are skilled at doing this is as beside the point as whether or not I can play “Sweet Jane” well. What matters about all this media-making is that they are doing it, and in the doing, they are able to understand so much more about how it works and what it means and how tough it is to do right — to say exactly what you mean, to be fair to people, to be heard and to be understood. If you find this exciting, and I do, it is not because you are getting some fresh tickets to the fame lottery; that’s the same game it’s always been. It’s because we are all getting a chance to tinker with and fathom the entire system that surrounds fame — and that shapes the news and entertainment we consume every day.

The Internet, with all its appendages, is one big stage. There is no script and no director. We cast ourselves. There’s no clear curtain rise or drop. Each of us has the chance to shine for an instant, to create a scene, and to embarrass ourselves. The house is crowded and moody and fickle and full of hecklers; sometimes people are paying attention to you, but mostly they’re not. And, let’s face it, the show itself is a mess. Yet there is so much to learn from the experience.

In the pre-Internet era, already receding into the murk, you couldn’t just step out onto this stage — the roles were rationed. To get one, you had to be lucky or wealthy or connected to the right people or so astonishingly good you had a shot at not being ignored. “Those were different times.” We assumed that those limits were eternal, but they turned out to be merely technical.

To this day, two decades after I first glimpsed a Web browser, this change knocks me flat and makes me happy. It doesn’t solve all our problems and it doesn’t fix everything that’s wrong with the digital world. But it gives us a bright ingot of hope to place in the scales, to help balance out everything about the Net and social media that brings us down — the ephemerality, the self-promotion, the arms race for your eyeballs, the spam, the tracking, the ads, and the profound alienation all of the above can induce when you tally its sum of noise.

This hope can be elusive, I know. It is deeply non-metric, invisible to A/B testing, and irreducible to data. It does not register on our Personal Digital Dashboards or vibrate our phones. It is still unevenly distributed, but it is more widely available than ever before. It lies in the gradual spread, one brain at a time, of a kind of knowledge about ourselves and one another that until very recently was held tight by a very small group that made mostly cynical use of it.

(One reason this idea remains relatively invisible in the conversation about social media is that so many of the journalists leading that conversation are professional cynics prone to missing its importance because of the nature of their work. Just as the things I learned about music by teaching myself “Sweet Jane” would be blindingly obvious to a professional guitarist, so the general public’s education in media basics thanks to the Internet elicits shrugs from most of the professional press. That doesn’t make it any less extraordinary.)

Any experience of authorship gives you a piece of this knowledge — the knowledge of the storyteller, the musician, the crafter of objects, the dreamer of code. In a media-saturated world that will eagerly tell us who we are if we let it, acquiring the confident insight, the authority of media-making, is both a necessity and a gift.

What is it that you learn from being a media actor and not just a media consumer? What do you come to know by playing a song and not just listening to it?

I don’t think the answer is reducible to bullet points. For me, two ideas stand out.

One is: Define yourself if you get the chance — if you don’t, others will be happy to do it for you.

The other is: Empathy.

IV. Anyone who ever played a part

Onstage that night in 2006, Lou Reed sure looked like he hated being there. For years afterwards, I kept that show filed in my memory under both “symbolic moments of despair” and “high-water marks of tech-industry hubris.” Today I’m a lot less certain, and much slower on the condemnation trigger.

Yes, the audience had sat there and essentially said: We’re rich and we’re building the future and we’re so cool that we can turn icons like Lou Reed into our private entertainment — and then not even pay attention to him!

And Reed? He responded with a big raised middle finger: “I’m here to serve,” he rambled, icily, during one song break. “It’s the moment I’ve been living for my whole life. I was on St. Mark’s Place and I thought, someday there’ll be a cyberspace, and an Internet…”

All that happened. And yet to frame the encounter as “philistine businesspeople vs. sellout artist” isn’t just reductive; I don’t think it’s accurate.

Remember: The Velvet Underground were famous for having failed to get the world to pay attention to them. Their live recordings, like the beloved Live 1969 album, have always sounded lonely. There are, maybe, three people clapping. The band’s albums sold miserably, to just a handful of devotees — though, as Brian Eno famously quipped, “every one of them started a band.”

I wouldn’t assume that Reed and his bandmates were indifferent to all this indifference. But it didn’t stop them from writing, or playing, or mattering.

I kept thinking about that strange collision-of-cultures show at Web 2.0 over the years, especially after the news of Reed’s death last year. What was he really thinking that night? Pestering Reed with questions about it is no longer an option. So I tracked down Jonathan Miller, then the CEO of AOL and the person who arranged the whole event, and asked him.

Miller and Reed met when Reed appeared in a 2002 AOL video shoot, and they studied with the same tai chi master. “We were trying for more of a presence on the West Coast,” Miller recalled. “We were the primary sponsor of the conference, and that gave us the right to designate a musical act for the night. I thought, we gotta have a little attitude. Lou embodies doing it your own way.”

So Lou Reed was going to lend AOL a little bit of his edge. Could be tricky! How pissed off was he, really?

“We went out for dinner afterwards,” Miller says. “He was okay with it. He said, ‘That wasn’t the first time I had to do that.'”

Neither Miller nor conference host John Battelle remembers (or will say) what Reed was paid for the show. Clearly, on some level, the performance was a simple transaction: Musicians have bills to pay, too, and today they have a harder time than ever — thanks in good part to the disruptions of the tech industry. If Lou Reed could earn a few bucks by renting out his attitude, who are we to throw stones?

On another level, it made absolutely perfect sense for Reed to be there at Web 2.0, talking to (or glowering at) the people building the media platforms of the future. In his own way, Reed was a geek, too, a connoisseur of guitar sounds, electronic gear, and audio experiments.

At the modest peak of his commercial success in the mid-’70s, he’d released a technologist’s dreamwork: a “difficult” double album titled Metal Machine Music presenting a symphony of pure feedback that is, depending on your opinion, either a groundbreaking work of pristine abstraction foreshadowing ambient and techno or a colossally bad joke that fell deservedly flat. (I think it’s kind of cool to write to.) In the late ’70s, Reed recorded several albums using a “binaural audio” technology intended to one-up traditional stereo. In Laurie Anderson’s moving piece eulogizing Reed, her partner and husband over two decades, she recalls the locus of their first date — a music-tech gear show. Patti Smith, in her tribute to Reed in the New Yorker, wrote, “An obscure guitar pedal was for him another kind of poem.”

So Reed could have been quite at home among the Web 2.0 crowd. But nobody felt at home that night — it was an orgy of awkwardness all around. See for yourself: 2006 was pre-iPhone, but there were some people in the device-forward conference crowd who kept their cameras handy, and crude videos of parts of the show turned up on YouTube. Here’s that Sweet Jane performance.

Pretty uninspired and uninspiring, no? What I see most, watching that clip and playing the event back in my memory, is Lou Reed having a lot of trouble, at that moment, being Lou Reed. So he falls back on tired mannerisms, a belligerence and cynicism that the songs he was performing had already transcended.

It never stops being hard to be yourself, whoever you are. To the extent that our time online gives so many of us space to work and play at doing so better, I’m grateful for it. I’m not going to hate it, even when it ignores me, or tracks my clicks, or lobs tomatoes at my face.

That night in 2006 was the last time I saw Reed perform in person, but it’s not how I want to remember him. I prefer this story, a recollection by film director Allan Arkush (as posted last year by Anne Thompson):

I asked Lou when it first struck him that he was indeed ‘Lou Reed.’ He told me that starting with “Transformer” in 1972, people came up to him on the street all the time and shared drug experiences or stories of being on the fringe of societal standards of behavior and how his music had inspired them to these extremes. Hearing those personal tales of decadence just made him uncomfortable and he did not like being the “Lou Reed” connection for only those types of experiences.

He told me a story of when he was most happy being ‘Lou Reed.’ It was in Manny’s Music Store (a very famous place where guitarist Mike Bloomfield bought the Fender he used on ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ on his way to that session, and countless other amps, guitars and basses that mark the history of rock were purchased). Lou was just hanging out, buying some new guitar strings, when he noticed that a young teen with his dad were shopping for his first Fender guitar. The kid was 13 or so and practically shaking with excitement as he had just put on the Telecaster and was being plugged in–a very serious part of the ritual of buying a guitar at Manny’s.

Lou was wondering what this geeked-out teen would play to test out his momentous purchase. After some tuning and a squall of feedback from being turned up to 11, the boy launched into the opening chords to “Sweet Jane”; the riff turned everyone’s head in the store. In his typical dry and penetrating manner, Lou looked at me: “That’s when I said to myself, ‘Hey. I’m Lou Reed!'”

For your listening pleasure: Visit the Sweet Jane Museum

I thought I came late to John Darnielle and the Mountain Goats. By the time I discovered them in 2004, they already had a dauntingly extensive catalog of tapes and albums under their belt. But it turned out to be good timing: they were on the cusp of a creative leap. Now I’ve been a fan for a decade (previous posts

I thought I came late to John Darnielle and the Mountain Goats. By the time I discovered them in 2004, they already had a dauntingly extensive catalog of tapes and albums under their belt. But it turned out to be good timing: they were on the cusp of a creative leap. Now I’ve been a fan for a decade (previous posts