Salon.com Wednesday announced plans to close Table Talk, the online discussion space and community that has operated continuously since Salon’s launch on Nov. 20, 1995. I was involved in Table Talk’s creation and management for its first several years, and when I read the news, I flashed back to my first day at Salon.

Salon.com Wednesday announced plans to close Table Talk, the online discussion space and community that has operated continuously since Salon’s launch on Nov. 20, 1995. I was involved in Table Talk’s creation and management for its first several years, and when I read the news, I flashed back to my first day at Salon.

As the tech-savviest of a not-tech-savvy-at-all gang of newspaper refugees trying to build a web magazine, I got pulled over by our then-publisher. He’d been tearing his hair out trying to get a group of unruly Cornell students to write the software that would power Table Talk, which was going to be Salon’s big bid for being not just an online magazine but an “interactive” website worthy of the Salon name. Things weren’t going well. “I want you to project manage this,” the publisher said. I thought, “What do I know from ‘project manage’? I’m a critic!” Then I dove in, because, in a startup with six employees, that was what you did.

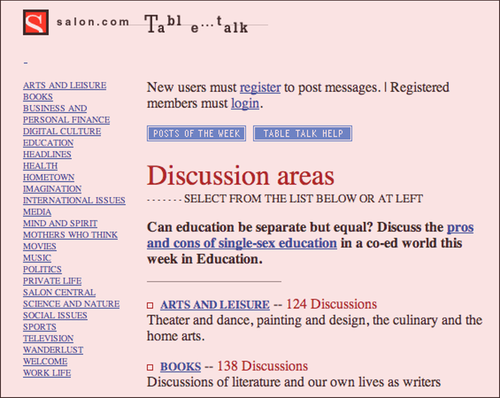

For me it was the start of a deepening engagement with and affection for the excitement, complexity and pitfalls of building software-powered websites. (Salon itself was lovingly hand-coded then and for several years after.) We got Table Talk launched, sort of, though within weeks we had to ditch the version those Cornell kids had built and start fresh. Said kids took their software and built TheGlobe.com with it, which went on to an impossibly successful IPO at the height of the dotcom bubble before a spectacular flameout.

The original idea was that every Salon article would have a link at the end to a Table Talk thread. The articles would serve, in part, as discussion-starters and then our community would kick the ideas around. It wasn’t a dumb plan — story comments are now a Web standard. But the way we built it, modeled on the experiences some of us had had as members of The WELL, Table Talk was a separate space with threaded discussions that anyone could add. The conversations weren’t tied to the stories very well, and we quickly learned that the community members — who took to the project avidly — preferred to talk about what they wanted to talk about. Salon’s editors and writers rarely hung out in TT, and it didn’t take long before the TT members developed a dysfunctional relationship with Salon’s staff — simultaneously craving our attention and resenting our presence.

So TT went its somewhat separate way from Salon-the-magazine, which soon started running a simple, hand-coded letters to the editor page to highlight actual responses to our stories. Mary Elizabeth Williams, its original and longtime host, managed the discussion space with great love and devotion for years. We all learned a lot about dealing with anonymity and trolls, personal authenticity and online performance art, technical woes and social dynamics.

What we never managed to do was find a way to knit the energy and talent of Table Talk’s remarkable community with the skills and money being invested into Salon.com itself. Instead, Salon tried over and over to find different models for tying community together with journalism. In 1999 it acquired The WELL. In 2002 it launched a blog program. In 2005 it transformed Letters to the Editor into a more web-standard comments feature. In 2008 it launched Open Salon as a modern, social blogging platform.

As a result, Table Talk became, more and more, a separate entity. When we started Salon Premium in 2001 as a paid service that let users see an ad-free site and some premium content, we rolled Table Talk into it: its pages were readable by anyone, but you needed to pay to post. That insured its survival but also assured its marginality. Over the years Salon’s management (which I was a part of until 2007) considered, over and over, whether to shut it down. It generated large numbers of page views from a relatively small number of users and advertisers were not excited by that. Its WebCrossing software was increasingly out of step with the direction the Web was moving in. Yet TT’s community remained close-knit and vibrant. In the wake of this week’s announcement, its members, unsurprisingly, are already trying to figure out ways to continue their conversations after the site’s announced June 10 shutdown date.

As a result, Table Talk became, more and more, a separate entity. When we started Salon Premium in 2001 as a paid service that let users see an ad-free site and some premium content, we rolled Table Talk into it: its pages were readable by anyone, but you needed to pay to post. That insured its survival but also assured its marginality. Over the years Salon’s management (which I was a part of until 2007) considered, over and over, whether to shut it down. It generated large numbers of page views from a relatively small number of users and advertisers were not excited by that. Its WebCrossing software was increasingly out of step with the direction the Web was moving in. Yet TT’s community remained close-knit and vibrant. In the wake of this week’s announcement, its members, unsurprisingly, are already trying to figure out ways to continue their conversations after the site’s announced June 10 shutdown date.

I don’t second-guess Salon’s leadership for deciding to end TT today — I might well do the same in their shoes. I do think there’s a lesson here, though, not just for Salon but for all the other enterprises out there today that dream of doing what we tried for so long to do at Salon. (Hi, Arianna; hi, Tina.)

The lesson is simple: Don’t think of “conversation” and “community” as subsidiaries to “content.” They aren’t after-thoughts, add-ons, or sidebars. They are the point of the Web. Here’s how I put it in Say Everything:

[Interactivity] is just a clumsy word for communication. That communication — each reader’s ability to be a writer as well — was not some bell or whistle. It was the whole point of the Web, the defining trait of the new medium — like motion in movies, or sound in radio, or narrow columns of text in newspapers.

Editors and publishers keep crossing their fingers and hoping to find some new platform that reverses this principle and puts them back in the comfortable realm of piping content out to consumers. They think this stuff will finally settle down. But change keeps accelerating instead. Today we are feeding one another stories, passing links around, telling friends what we’re fascinated by or excited about or steamed over. My Flipboard is more useful and interesting to me than the front page of the New York Times (sorry, Bill Keller). The conversation isn’t an after-thought. It’s interesting in itself, and it’s how we inform one another.

So Table Talk is dead: RIP. But Table Talk is everywhere, too — on Facebook and Twitter, all over the blogosphere, and in a billion comment threads. Table talk is what we do online. It’s not what comes after a publication’s stories. It’s what comes before.

BONUS LINK: If you haven’t already, go read Paul Ford’s wonderful essay on the nature of the Web and its fundamental question — “Why wasn’t I consulted?”