I had such a great time at South by Southwest last spring talking about blogging that I threw my hat in the ring again for next year.

My idea this time: “The Internet: Threat or Menace?” — a guided tour through two decades of tirades, fusillades and rants against the Internet, the Web, and all the other stuff people do with computers.

There’s rich history here, much of it already forgotten, some of it extremely funny. I’ve read a lot of these books and essays already. I’m eager to try to figure out why so many Internet critiques have that undead-zombie quality: you know they’ve got no life left in them, yet they keep lurching forward, leaving trails of slime for the rest of us to slip on. Yes, of course, there are legitimate and valuable critiques of the Net and what it hath wrought. And a reasonable amount of fatuous utopian hot air as well. I will lay it out and we can all roll our eyes together.

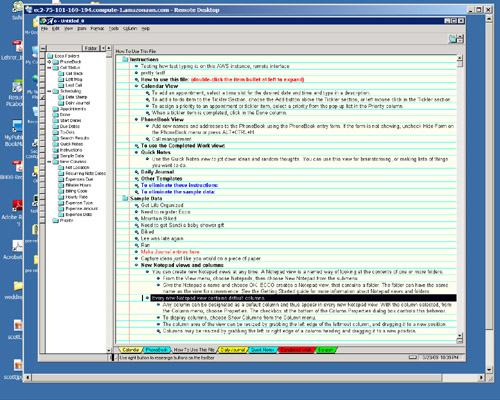

If you want to give me a chance to do this, you know the drill: hie thee PanelPicker-ward and cast your ballot. And spread the word. I will be grateful. If I am picked, I will enlist all of you as collaborators here as I try to stretch my arms around this vast topic.

But I’ll understand if you’d rather just sit back and let me do all the work.

And if enough of you vote, I will attempt to distill the material to its essence.

In haiku.

Oh yes. Many other fine people are proposing interesting sessions at SXSW. Here’s a handful I’ve come across that I recommend to you:

Justin Peters of CJR running a panel on “Trust Falls: Authority, Credibility, Journalism, and the Internet”

Mother Jones’ panel on “Investigative Tweeting? Secrets of the New Interactive Reporting”

Jay Rosen’s “Bloggers vs. Journalists: It’s a Psychological Thing”

Dan Gillmor on “Why Journalism Doesn’t Need Saving: an Optimist’s List”

Steve Fox assembling a panel on “That Was Private! After Weigel does privacy exist?”

My friends at XOXCO have a couple of proposals: Ben Brown on “Behind the Scenes of Online Communities” and Katie Spence with “Tales of the Future Past: Web Pioneers Remember.”

And tons more that I’m sure I’ve missed…