Apparently there was a big meeting of news executives today in Chicago under the auspices of the Newspaper Association of America. The de jure name for the topic at hand was “Models to Monetize Content” but the de facto subject of the conclave seems to be building paywalls and ending what James Warren glibly calls “the age of content theft.” Such conversation needed to take place under the watchful eye of a legal counsel to avoid antitrust problems; but who can doubt that some sort of collective action — simultaneous, if ostentatiously uncoordinated — is at hand?

We are, then, nearing a moment of real decision on the part of the beleaguered newspaper industry, a genuine fork in the road. The papers can decide to keep participating in the open Web, which would require accepting that their legacy business — the old paper bundle and the broadcast model — is going to change into something almost unrecognizable. Or they can decide to put up the walls and gates and behave as if it’s 1997 again, and the Web is just a better delivery truck rather than an intricately evolving social organism. Down one path, dissolve into the Web; down the other, secede from the Web.

These two paths map neatly onto the two camps into which you can group virtually everyone in the old argument about the news business and the Web. On one side, you have the people who feel that newspapers simply took a wrong turn on their journey to the Internet. They were seduced by the Web hypesters! They should have charged for their articles from day one! Because they didn’t, they’re in a bind now — but their only hope is to shut the door belatedly and salvage what can be salvaged. We heard this same cry back in 2000-2002, during the last Web-business ice age.

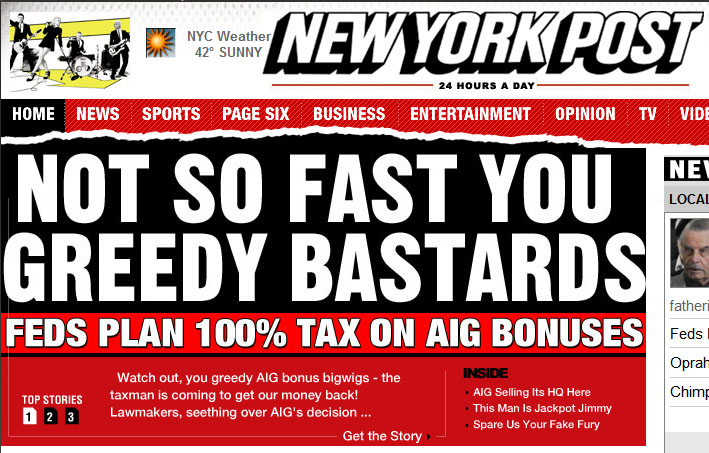

If this is what you believe, then the appropriate business strategy is a no-brainer: Start charging your readers. Start demanding that Yahoo and Google et al. pay to link to you. Then see what happens — and, I’d advise, duck as the masonry starts to crumble.

In the other camp, the one where I put my own tent, you find everyone who believes that the Web has radically and irreversibly changed the way people get their information, weakening or dismantling all of the buttresses and structures that held the old business of media together. This change is neither all good nor all bad; but it is real, and wishing it away won’t help.

I’ve argued this position consistently for years now, but here is another angle worth considering. In at least one area, the newspaper web sites of the 90s didn’t give away the store. The Web was an obviously superior platform for delivering classified ads, but newspapers traditionally made a good chunk of their revenue from classifieds, so many newspapers adopted a sort of half-hearted classified strategy: if you paid for a print classified ad, you got a web listing free. Or maybe the paper would sell you a Web classified at a different rate from a print classified.

So, in this realm at least, the papers never committed that original sin of offering their product for free. What happened? The papers mostly sat tight and figured that their brand and their prominence in their communities would outweigh the lameness of their software and their indefensible overcharging for a product that now cost little or nothing to deliver. There were big venture-funded startup companies that set out to build standalone classified businesses, and some of them prospered as for-profit enterprises. But the greatest success of all came in the unlikely form of Craigslist, a community-based enterprise led by a shy programmer who offered classifieds not as a profit-making enterprise but (in all but a tiny subset of categories) as a free service.

As a result, newspapers’ classified businesses today have been devastated. But you can’t blame Craig Newmark; if he hadn’t done it, others would have, in some slightly different form. The Web itself made that inevitable. Newspapers had the opportunity to be Craig Newmark; they couldn’t imagine that. Regrettable, but understandable.

Similarly, you can blame Wikipedia for the woes of Encyclopedia Britannica’s paper-edition business, but really, it was less that unforeseen project that doomed the bound-volume encyclopedia than the very existence of the Web itself, which gave people an ill-ordered but livelier source for much of the information they sought.

In each of these cases, no one gave the store away. The shopkeepers didn’t play along, they tried to fight. But the scope of Web-induced change made their battle mostly hopeless. And their choice to fight the Web rather than work with it meant they only hastened their own downfall.

Similarly with the pay-wall argument. I fear that if our newspaper publishers take the collective charge-our-users approach, they will not only doom their own enterprises but will also make the transition we are currently facing — from a paper-and-broadcast news world to a purely digital one — longer and more wrenching.

If news publishers today accept that their future is online and that said future will not and cannot offer the same profit margins, or support the same size staff, as a monopoly, they can still participate in building new models for the new world. Some will survive and some will fail, but all of them (and all of us) will benefit from the lessons they can teach us. But if they shunt themselves off behind pay walls, they will not only surely fail, they will also make it far harder to seed the Web with the knowledge and experience of today’s professional journalists. The work of newsroom professionals will be cordoned off into their own disconnected islands online that fewer and fewer people will visit. New traditions will evolve independent of the old ones.

I can understand that news publishers — the owners and stockholders and managers — will do everything they can to cling to a failing model, because that is the way of the business world. A revenue stream is a revenue stream; it’s hard to give it up today, even when you know it’s going away tomorrow. But the journalists who care about their own craft’s values and traditions should think twice before applauding the intransigence of their business colleagues. In the long run, it will do nothing to save their jobs. And it will make it that much harder for all of us to rebuild a vibrant and sound news tradition online.

UPDATE: Recommended reading — Steve Buttry on “Seven reasons charging for content won’t work”