Like nearly everyone else in the journo-blogosphere I have been reading writer Dan Baum’s account, on Twitter, of how he got fired by the New Yorker. It is a canny PR move on Baum’s part, and the New Yorker is a fascinating enough institution that a little glance under the tent flap is hard to resist. But aside from getting a lot of extra attention, and helping promote a new book, why did Baum deliver this confessional kiss-off via Twitter?

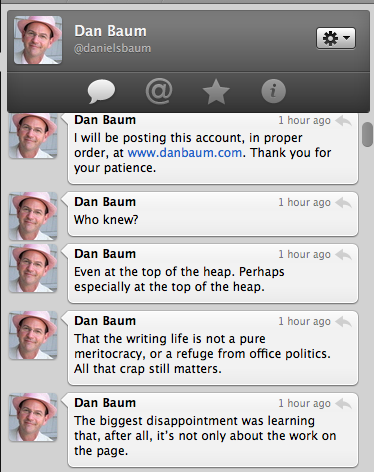

He didn’t use Twitter in any particularly creative way, and now he says he’ll be “posting the account, in proper order,” on his website. So he’s admitting that the reverse-chronological ordering on Twitter is “improper” — it makes it harder to read the tale. Why Twitter it at all?

The answer lies in what I will call Rosenberg’s Law of New Media: Each new media form invites a new round of “firsts” that the older media will over-cover. You can see this in action from the first arrival of online interaction pre-Web, to the rise of the Web, to the rise of blogging, and now with the Twitter craze: First there was the first couple to marry who’d met on the WELL. Then there was the first couple to marry who’d met on the Web. Then there was the first couple to marry who’d met in comments on a blog. And any day now I’m sure we’ll learn about the first couple to marry who met via Twitter. (Maybe it happened already and I missed it.) And each “first” becomes the hook for some breathless story. First book deal! First company founding! First suicide!

So Baum is just shrewdly exploiting this law, gathering a crowd for his little tell-all. Can’t blame him for that. But I wish that, having gathered such a crowd, he had had something more illuminating to say.

A couple years ago Baum’s New Yorker contract wasn’t renewed, and he believes this was not because of the quality of his work but because New Yorker editor David Remnick took a dislike to him. He has posted the articles Remnick rejected so you can decide for yourself. And he offers, as a lesson from it all, the following jaw-dropping moral:

“The biggest disappointment was learning that, after all, it’s not only about the work on the page. That the writing life is not a pure meritocracy, or a refuge from office politics. All that crap still matters. Even at the top of the heap. Perhaps especially at the top of the heap. Who knew?”

My reaction to reading this observation is: If I were your editor and you ever said anything like that to me, I’d seriously consider firing you on the spot. No reporter can afford this level of naivete, and no editor’s budget should be spent on it. Reporters have to understand the world pragmatically, as it is, in all its mess and compromise; how can you trust a reporter who doesn’t even understand how his own profession works?

I spent the early part of my career as a freelancer writer, and every time I was rejected I wondered what was wrong with me and my work. Later in life I wound up for many years on the other side of the equation, as an editor, accepting and rejecting pitches and sitting in editorial meetings debating ideas. And I learned what everyone who’s done that knows: editors have to say “no” many more times than they can say “yes,” and they can’t always tell writers the reason behind the “no.” Sometimes it has nothing to do with the writer and his work; and when it does, telling the whole truth can be hurtful.

It’s hard to say to a writer, “You’re sloppy” or “You’re just not original enough” or “Your sensibility just doesn’t fit here.” Most editors don’t. The same principles apply to the hiring and firing of staff writers (New Yorker writers like Baum are typically on year-long freelance contracts); if anything, honesty is even harder in those cases.

I think none of this is news to 95 percent of people working in 95 percent of newsrooms, nor should it be. I could imagine some young writer at the start of his career imagining the New Yorker, or any other top-flight journalistic organization, as a pure meritocracy. But for an experienced mid-career magazine writer like Baum, it suggests some sort of disconnection from reality.

(There’s also this strange business of the double-byline that isn’t: On his website Baum says that all of his work is a collaboration with his wife, Margaret Knox, and that “everything that goes out under the byline ‘Dan Baum’ is at least half Margaret’s work,” but he gets the bylines because — I dunno, you read the explanation and see if it makes sense to you. Seems at the least awfully retro to me, and at the worst, pretty unfair both to Ms. Knox and to the couple’s readership.)

I don’t know why Remnick fired Baum. Maybe Baum’s pieces really didn’t fit into the New Yorker as Remnick envisions it. Or maybe, as Baum has it, it was just a personal dislike on the New Yorker editor’s part. But Baum’s clueless tweet made me think there might be more to Remnick’s side of the story. Which, quite properly, we’ll probably never know.

Post Revisions:

- May 12, 2009 @ 10:17:19 [Current Revision] by Scott Rosenberg

- May 12, 2009 @ 10:09:07 by Scott Rosenberg

- May 12, 2009 @ 10:02:12 by Scott Rosenberg