Over the weekend many news organizations reported, erroneously, that Rep. Gabrielle Giffords was dead. These reports don’t seem to have originated on Twitter. But many spread there — and now they’re occasioning a round of head-scratching over how to handle retractions and corrections in this new communications format.

This happens with every new phase of communications-technology evolution. Twitter, with its speed and popularity and intermingling of professional and personal channels, presents some modest new challenges to accuracy practices. But for journalists there should be little confusion about the answers.

At Lost Remote, Steve Safran writes:

We ask: is deleting a tweet after the fact a lack of transparency, especially if any subsequent tweets don’t admit the error? Is a news organization obliged to tweet that it was wrong? Does the retweet function make such actions moot? We strongly believe in transparency, as do many of you. But whether deleting tweets is a responsibility or not, and whether a news organization must tweet that it was wrong, should lead to serious discussions in all newsrooms.

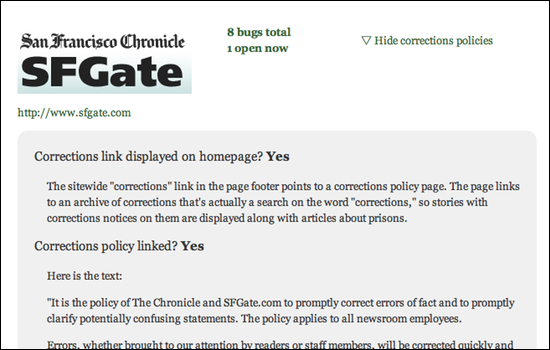

For a private individual using Twitter, it might make sense to delete a message that you later discovered was in error. But for anyone tweeting as part of a professional media job, representing a news organization on Twitter, or using Twitter to do journalism independently, the course here ought to be plain: It’s almost always better to correct than to unpublish. Removing information you’ve already disseminated — sometimes called “scrubbing” — always leaves open the possibility that you’re trying to hide the error or pretend it never happened.

The folks at WBUR have it just right:

We have decided NOT to delete the erroneous tweet, because it serves as part of the narrative of this story. Facts can change fast when news is breaking, and that leads to errors. We need to own the error, not hide from it. But we also need to rectify the error and explain ourselves to people who trust us. Deleting the tweet would do more to harm trust than preserving it would do to harm truth.

According to the chief argument in favor of tweet-deletion, if you leave a bad report lying around your feed, you’re tempting others to retweet it; if you delete, you’ll inhibit this viral repetition of misinformation. That’s a reasonable position. But there are alternatives to simply zapping the bad tweet and scrubbing the record.

The same technologies that force these problems on us can also help us solve them. On the Web, for instance, publishers can use versioning tools to keep a corrected edition of a story front and center while maintaining a trail of accountability. Similarly, Twitter users can use Twitter itself to correct the record while preserving it.

For instance: say your newsroom had sent out a tweet that read, as NPR’s did:

BREAKING: Rep. Giffords (D-AZ), 6 others killed by gunman in Tucson

You could send out a followup message, preserving a record of the error while correcting it:

CORRECTION Giffords wounded, in critical condition RT @NPR BREAKING: Rep. Giffords (D-AZ), 6 others killed by gunman in Tucson

Then you could reasonably go back and delete the original. This might be a useful tactic to curtail the spread of bad info. But it still flattens the record a bit, since the original message’s timestamp (and possibly other contextual data) would vanish.

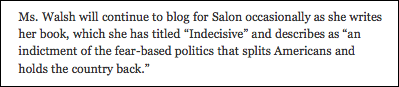

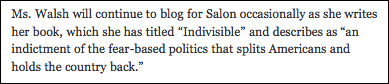

Better yet is the idea floated by “Being Wrong” author Kathryn Schulz (@wrongologist) in this Poynter interview by Mallary Jean Tenore: “Why not have a ‘correct’ function (like the ‘reply’ and ‘retweet’ functions) that would automatically send a correction to everyone who had retweeted something that contained an error?”

Such a tool would dragoon the engine of viral misinformation back into the service of truth. You can say, “Hey, it’s just Twitter, what’s the big deal,” but experience suggests that arguments about Internet tools that begin with “It’s just” will get disproved over time. Twitter is beginning to mature into the rapid-response nervous system of our news world. It needs and ought to have a function like the one Schulz proposes.

BONUS LINK: Craig Silverman has a valuable roundup of links relating to errors in Tucson shooting coverage.

[I’ve continued discussing this topic in a followup post.]