If you want to hear from me over the next few days and you are in the Bay Area, you have a bunch of opportunities.

Friday I’ll be presenting at Stanford Law School’s conference on “The Future of News: Unpacking the Rhetoric” (as I wrote here). I look forward to unpacking a lot of rhetoric there; my suitcases are full and I definitely would like to travel more lightly. Seriously, there’s a great lineup there and I don’t think it will be the usual vague rehash of tired old tropes.

Saturday, I’ll be speaking at WordCamp SF. I’m thrilled about this, partly because I love WordPress, partly because I’ve had a great time at the two previous WordCamps I’ve attended, and partly because I’m talking about blogging’s place in our culture and WordPress’s place in the history of blogging (which I really didn’t get deeply into in Say Everything) — and after all this time I still love talking about this stuff.

Sunday, I’ll be at Journalism Innovations III and RemakeCamp, speaking about MediaBugs as one of a gazillion fascinating projects in journalism that people will be presenting there.

Come on down if you can, and definitely say hi if you do!

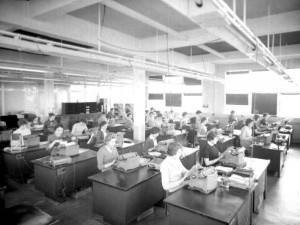

This sweatshop approach to content creation is, of course, anathema to old-fashioned writers and editors. It raises all sorts of disturbing questions about the advertising cart leading the editorial horse (as

This sweatshop approach to content creation is, of course, anathema to old-fashioned writers and editors. It raises all sorts of disturbing questions about the advertising cart leading the editorial horse (as