A new study examines the interplay of mainstream news outlets and blogs in forming the news cycle. One of its findings is that, as a report by Steve Lohr in today’s Times puts it, “For the most part, the traditional news outlets lead and the blogs follow, typically by 2.5 hours.”

This story won’t buck that trend. Lohr’s piece was posted online last night and my post here follows by about 10 hours or so. One reason for this is that I slept through the night. Another is that I decided to actually read the study before posting.

The study — Meme-tracking and the Dynamics of the News Cycle, by Jure Leskovec, Lars Backstron and Jon Kleinberg — is fascinating work; though I’m not qualified to assess its math, I found it careful and thoughtful in its approach to the subject. But before its core finding coalesces into a hardened soundbite — “pros beat bloggers by 2.5 hours!” — I want to offer some cautions and raise some red flags.

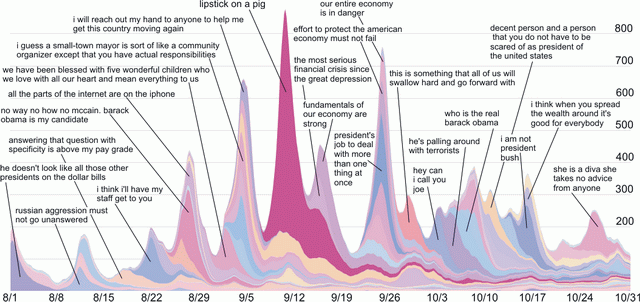

The most important caveat is that the study isn’t really tracking “news.” It looks at the propagation of specific quotations in news and blog coverage of the final three months of the 2008 election cycle. In other words, it’s tracking soundbite phrases — like “lipstick on a pig” and “palling around with terrorists.”

Such phrases are sometimes proxies for real news but most often they’re just part of the partisan slagfest. The memetracker study emphasizes the trivial at the expense of the substantive. In its world, if there’s no brief quotation that sums up a particular story, the story doesn’t exist.

Last fall, surely, the biggest story of all was the near-collapse of our financial system. In the study, this story is represented by a few phrases like “our entire economy is in danger” and “fundamentals of our economy are strong.” While these phrases are reasonable ways to track the language the candidates used to discuss the crisis, they don’t provide any hooks for understanding the extraordinary outpouring of explanation and analysis of an extremely complex story in both the mainstream media and the econo-blogosphere.

The researchers find that the news cycle is governed by two factors: “imitation” and “recency.” In other words, phrases rise in prominence because media and blogs copy one another, and fall as individual phrases age. This is a useful model, but it leaves no room for valuing originality in coverage. (No surprise, since it’s looking exclusively at quotations.) Both traditional news organizations and bloggers place great value on getting a story that no one else has, or expressing a point of view that can’t be found anywhere else. Most of us — bloggers and pro journalists alike — assume that originality drives attention. But the memetracking research is biased against originality, and it simply excludes material that doesn’t hang off the soundbite quotes of public figures, so it offers no help assessing whether we’re right in that assumption.

One of the central argument of my book Say Everything is that blogs have enhanced our culture by extending the width and depth of public dialogue. But the memetracker researchers’ focus on quoted phrases excludes such contributions.

As for that 2.5-hour lag: since the study focuses on quotations as a sort of genetic marker for ongoing news threads in election coverage, of course the traditional media are going to have the jump on bloggers. They’re following the politicians around with microphones and notebooks. The study did find that, 3.5 percent of the time, phrases are injected into the news cycle first by blogs and then picked up by traditional news outlets. It’s certainly possible that this pattern would be found to apply outside of election news, and with a wider set of stories than those defined by political quotations. But we don’t know that.

Another limitation of the study: It misses the interplay between both traditional media and blogs on the one hand, and the two other vast channels through which soundbites propagate, cable news outlets and social networks like Twitter and Facebook.

Finally, the study relies on Google News to draw a boundary between the news media and blogs. A site that appears in Google News is considered media; everything else is a blog. While this approach is convenient, it ends up slicing off some of the top layer of the blogosphere in arbitrary ways: for instance, Gawker and Daily Kos end up as “media” rather than blogs, but Talking Points Memo is a blog.

I think the study’s authors are being careful about not overreaching in their claims for their research. Kleinberg tells Lohr: “You can see this kind of research as further elevating the role of sound bites… But what we’re doing is more using them as the approximation for ideas and story lines… We don’t view quotes as the most important object, but algorithms can capture quotes.”

Nonetheless, I fully expect to see it taken as conventional wisdom from this point forward that “news starts with the traditional media and then moves into the blogosphere.” Perhaps the Memetracker folks can follow the phrase “2.5 hours” and show us exactly how that happens.

[You can find neat visualizations of the data from the study at a companion site, memetracker.org, from which I inserted the image at the top of this post.]

BONUS LINK: Chris Anderson outlines his research into the news cycle. Anderson took one story, followed it through the maze of coverage online and in print. It’s what he calls a “qualitative” approach to complement the Memetracker study’s quantitative work.

UPDATE/CORRECTION: I wrote above that Talking Points Memo would be considered a blog by the study because I couldn’t find any posts from it on Google News, but Zach Seward at Nieman Lab did (here). I’m further confused by the study’s description of the list of “early reporters” of many stories as being “blogs and independent media sites” including HotAir.com and Talking Points. This whole business of dividing the world between blogs and traditional media is, as Mark Glaser argues in the comments to Seward’s piece, increasingly difficult to pursue or defend.

I was cleaning out my garage recently, combing through some old files, and stumbled on a research paper I wrote in 1981 as a senior in college. The title was “The Electronic Newsroom and the Video Display Terminal.” I was writing about the moment that the digital transition rolled out from the back shop to engulf the newsroom, as — almost overnight — the typewriters were put out to pasture and a generation of journalists learned to love cut/paste and the “delete” key. What would that mean for the future of news?

I was cleaning out my garage recently, combing through some old files, and stumbled on a research paper I wrote in 1981 as a senior in college. The title was “The Electronic Newsroom and the Video Display Terminal.” I was writing about the moment that the digital transition rolled out from the back shop to engulf the newsroom, as — almost overnight — the typewriters were put out to pasture and a generation of journalists learned to love cut/paste and the “delete” key. What would that mean for the future of news?