I pretty much stopped writing on this blog about a year ago, and never wrote up why.

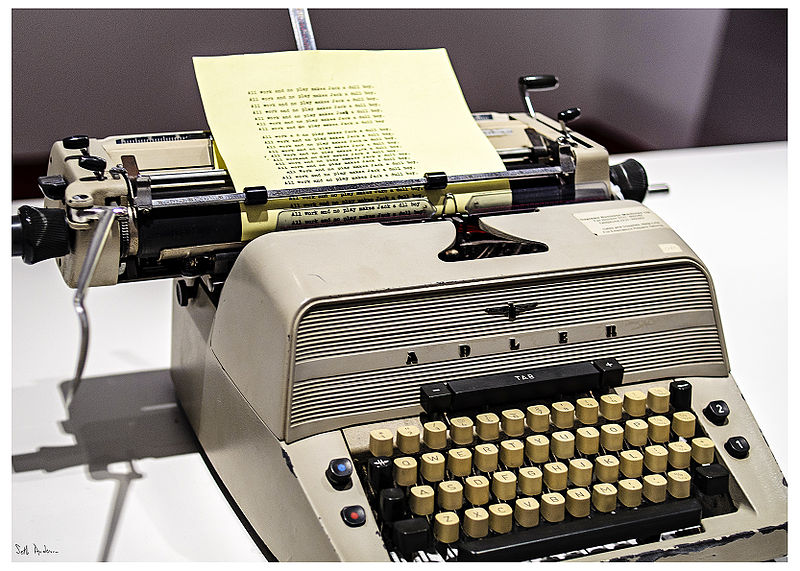

Last year I relaunched Wordyard as “The Wordyard Project” with a new design, lots of energy, and a focus on the topic of identity and personal authenticity in digital media. I felt like I had a lot to say that I’d stored up during the years I spent editing Grist, and I began writing. I had fun! In particular, I was obsessed with writing one piece I’d been thinking about for ages — about Lou Reed, the song “Sweet Jane,” hearing Reed play that song at the Web 2.0 conference a decade ago, and how all of that related to life on the Internet as I’ve lived it for the past 20 years.

So I wrote that piece. Then I kept writing. But I lost steam. It seemed to me I was repeating myself. Looking back at the posts from that period now, I don’t think I was. But that’s how it felt.

That was the personal dimension. At the same time, in the wider world, I understood that blogging was a very different beast in the mid-2010s than it had been a few years before: not “dead” but less and less an environment where writers were congregating and software developers were innovating. I didn’t want that to be true, but it was: The conversational aspect of blogging had largely been assumed by Twitter and Facebook. If you aimed to build traffic on a blog today, you had to treat it like a publishing venture — keep pumping out lots of posts and promote them tirelessly on social media.

All of which, at that point, felt to me like more repetition.

One of the first things we learned about publishing online from the earliest days — when Hotwired ruled, Suck.com flourished, and Salon (a “Web ‘zine”!) fledged — was the imperative of repetition. I remember my colleague Andrew Ross talking about how the Web was a little like radio. He meant you could be a little more casual; you could, when news broke, just ring up an expert for a quick Q&A without waiting to assemble a more definitive story. He was right. But it was also like radio in the way you needed to remember that people were probably tuning in and out all the time, and you were going to have to repeat yourself a lot to be heard.

I’ve been writing reviews and news stories and features and columns and blog posts all my life. There are times when cranking it out is effortless, and other times when it just feels impossible. When I go through a spell of those impossibles — as I did toward the end of my days writing theater reviews, and again toward the end of my years as Salon’s managing editor, and again in autumn 2014 — I know that the best thing for me to do is to move on, change things up, try out something new. That works. But when I do it, I’m also always gnawed by the suspicion that maybe I’m just running away from what I Should Be Doing.

It’s a tough one: On the one hand, as David Byrne once sang, “Say something once! Why say it again?” On the other hand, that song is titled “Psycho Killer,” and maybe the narrator is…unreliable.

So I put Wordyard on hold, where it’s been ever since. Around the same time I also started writing some reasonably ambitious pieces for Steven Levy at Medium’s Backchannel, and those kept me busy, and felt rewarding in a different way, and let me focus on simply writing as good a piece as I could without also thinking about how to get people to come read it.

Am I going to return to any kind of posting schedule here? I honestly don’t know. I’d like to. I’m a big believer in the IndieWeb movement’s “POSSE” principle — publish on your own site, syndicate everywhere — meaning, you have a site that you own and cultivate and then you share your work in all sorts of other venues as you wish. I dream of software to make that even easier than it already is. (I like what the folks at Known have accomplished in this direction already.) I have all sorts of ideas for experiments in this area. Let’s see how far I get.

In the meantime, what I am doing today is taking that “Sweet Jane” piece and reposting it on Medium, where maybe a somewhat different bunch of readers might see it. It still says so much of what I want to say.