This month I have watched with fascination the unfolding of what future historians may dub the Great Reverse Engineering of the Facebook algorithm.

It is a noble and important effort! I applaud those who have labored valiantly in its trenches. And I also have to say: It's doomed, hopeless, a dead-end street.

Here's what's been going on: People are playing public games with Facebook in an effort to get a finer-grained understanding of how, exactly, the newsfeed algorithm decides to hoist or bury individual postings.

To wit: Caleb Garling wrote in the Atlantic about his effort to trick Facebook into displaying a post more widely by sprinkling it with ringer language. "Hey everyone, big news!!," he wrote. "I've accepted a position trying to make Facebook believe this is an important post about my life!" Sure enough, the post went into heavy rotation.

Garling's post was content-free — an elaborate self-referential stunt. Next, media scholar Jay Rosen started applying the same technique as a tactic for boosting the visibility of his posts on the future of journalism: "Big news in my family! (You can ignore that. Just messin' with the FB algorithm so maybe you will see this.) I have a new post up at my blog, PressThink." It seemed to work pretty well.

Meanwhile, Wired's Mat Honan conducted an experiment to see what would happen if he "liked" everything he encountered on Facebook for 48 hours. He fell into a rabbit-hole of alienation, and discovered that there is no end to the like — it is an infinite loop.

Elan "Schmutzie" Morgan took precisely the opposite tack, forswearing all use of the "like" button. Morgan found that removing the "like" option from her palette forced her to connect more substantively by writing actual comments on posts if she wanted people to know what she thought:

It seems that the Like function had me trapped in a universe where the environment was dictated by a knee-jerk ad-bot… Now that I am commenting more on Facebook and not clicking Like on anything at all, my feed has relaxed and become more conversational. It’s like all the shouty attention-getters were ushered out of the room as soon as I stopped incidentally asking for those kinds of updates by using the Like function.

One inspiration for all these experiments is the long-term success that outfits like Buzzfeed and Upworthy have found in plumbing the mechanics of virality. Another, I'm guessing, was an event at Harvard's Berkman Center last month, at which scholars talked about the results of a "collaborative audit" of the Facebook newsfeed algorithm.

Their findings were fascinating, but the single most important result was also the simplest: a majority of the people in the study didn't have a clue that Facebook filtered their newsfeeds at all. That should give the rest of us pause: While we struggle to fathom the nuances of Facebook's post filters, it seems likely that a vast number of users don't even understand that their feeds are shaped to begin with. So there’s one beneficial side-effect of these various experiments in fooling Facebook’s machine: they help make people aware of the machine’s presence.

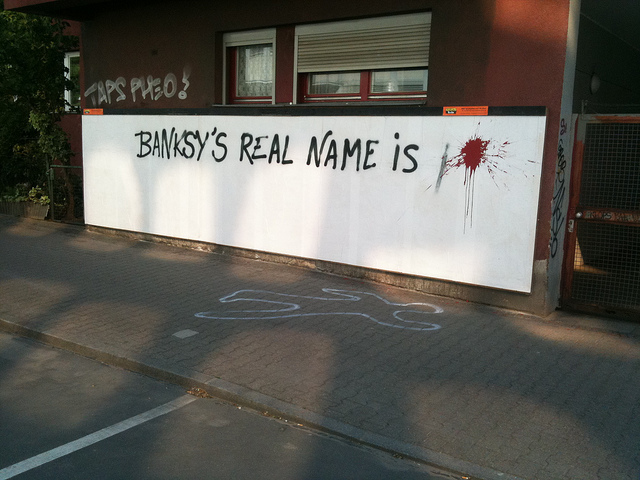

But the biggest problem with the reverse-engineering project is that we are not studying some natural phenomenon or physical product. The newsfeed algorithm is malleable software that's mutating all the time. The harder we game it, the faster its operators will change it.

An algorithm’s flexibility is one of its great strengths. Facebook’s changes for all sorts of reasons — including the well-intentioned efforts of Facebook developers to improve users' experiences, the competitive demands of the social-media marketplace, and the specific needs of Facebook-the-corporation to satisfy shareholders.

But the algorithm also moves in specific reaction to just the sorts of reverse-engineering projects I've compiled here. Any edge you can build by faking Facebook out isn't going to last long. A decade's worth of SEO-expert experience with Google bears this out. It's a game of Whac-a-mole that's rigged in favor of the platform owners, who have a direct line into the code that the rest of us are just speculating about.

Rosen, like many other journalists, expresses a preference for Twitter's structure, which by default shows you all the updates of every user you've chosen to follow. That makes it more transparent and gives users more direct control over their informational diet. There’s less guesswork involved, and that gives it far more value for sharing news.

But you can't count on it to stay that way. Twitter looks likely to evolve in Facebook's direction — it has shareholders to satisfy, too.

In any case, the longer we play this cat-and-mouse game with the social network operators, the clearer we can see that we are the mice. The experiments we perform from the insides of our Facebook compartments will grow increasingly desperate — like the ruckuses prisoners create as they try to capture or divert the attention of their jailer. But they'll never give us answers we can rely on.

All the reverse engineering in the world won't solve our deeper problem as users and builders of digital networks. The more we depend on such networks for our information, our social connections, our government and our entertainment, the more vital it becomes for their workings to be transparent, fair, and organized for the public good — and the less willing we should be to subject ourselves to the vagaries and whims of fickle companies. (This week, for instance, Twitter — which has touted its free-speech credentials — decided to censor controversial images of a reporter’s beheading. The images are loathsome; but do we really want Twitter-the-company to make these calls for us?)

Services like Facebook and Google don’t share the details of their algorithms because that code is their “secret sauce.” We’ve all heard that cliche. Secret sauce can be tasty. But if it's a big part of your diet, sooner or later, you're going to need to want to get a full breakdown of the ingredients.