When we say something is “real,” we usually mean there is something irrefutably solid and constant about it. Reality, as Philip Dick famously said, “is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” It is the stone you kick when — like Dr. Johnson refuting Bishop Berkeley — you need to escape abstraction for solid ground. And kicking it hurts.

When we say something is “real,” we usually mean there is something irrefutably solid and constant about it. Reality, as Philip Dick famously said, “is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” It is the stone you kick when — like Dr. Johnson refuting Bishop Berkeley — you need to escape abstraction for solid ground. And kicking it hurts.

But when it comes to human expression, our sense of what’s real is anything but constant. Our conception of the sound of a “real voice” is in constant flux. This is true not only in terms of actual audio recordings (where Greg Milner’s excellent Perfecting Sound Forever offers a fascinating tour of the changes in technology and fashion across the decades) but also for writing styles, art and design, film and theater, politics, and of course advertising. One generation’s “telling it like it is” becomes the next’s boring countercultural cliche. The revolution will always be commodified.

One key I’ve found to understanding the dynamics of this process is the concept of the authenticity bind. Jefferson Pooley’s essay “The Consuming Self: From Flappers to Facebook” introduced me to this idea. It’s an engrossing slice of intellectual history and cultural criticism, first published in 2010 but still fresh and more relevant than ever. I’m planning on posting a Q&A with Pooley in the near future digging deeper into the whole topic — it’s central to the stuff I aim to cover here. But first I just want to lay out the premise, because it’s worth its own post. (The essay isn’t available as a digital text but you can get a PDF from Pooley’s site here.)

Pooley traces the history of personal authenticity through the lens of a mid-20th-century American intellectual tradition — thinkers such as David Riesman and Christopher Lasch. He outlines “the contradiction that is at the core of the modern American self,” which “could be summed up as: Be true to yourself; it is to your strategic advantage.”

Our culture, Pooley writes, summons us to “embark on quests of self-discovery that promise to affirm our uniqueness”; then the “self-improvement industries and especially advertising” hitch along for the ride, or hijack the quest for their own ends. The same culture also commands us to “stage-manage the impressions we give off to others as the essential toolkit for success” — to cultivate our personal “brands.”

The contradiction between self-promotion and expressive distinction, bound up as it is with a highly adaptive market economy, is in fact self-feeding. That is, the pervasiveness of what might be called “calculated authenticity” leads…to rejectionist forms of authenticity — real authenticity, untainted by the professional smile and the glad hand. These flights to deeper kinds of authenticity are, however, marketed in turn — returned, that is, to the promotional fold. The result can be thought of as an “authenticity bind.”

Choosing to be as Pooley puts it, “instrumental about authenticity” — being yourself because, man, it sells — creates a paradox. It’s like the paradox of the businessperson who learns to meditate on the futility of striving because it helps him close deals. You can make this kind of thing work for a while, but sooner or later it will catch up with you.

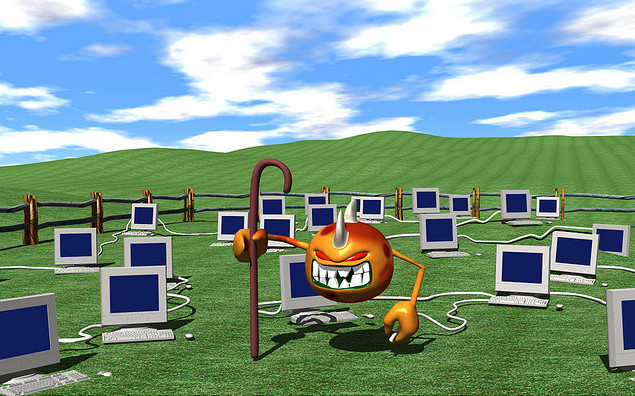

The challenge of the authenticity bind might once have been primarily of concern to celebrities and public figures. But the growth of online culture and the rise of Facebook — which Pooley describes as a “calculated authenticity machine” — have put us all in the same boat.

When I first read “The Consuming Self,” it seemed to me that Pooley had connected some important dots, and begun to give us a handle on how to think more clearly about what it means to “be yourself” online. The essay offers doses of both fear and hope. The scary part is that, if you buy the logic of the authenticity bind, there’s really no way to fully escape it. The hopeful part is that, if you understand how “calculated authenticity” works, at least you won’t be ambushed by it, and you might be able to mitigate it.

In my next post I’ll begin to lay out one path where I see some prospect of transcending the authenticity bind — not wriggling entirely free, but perhaps loosening the ropes a bit.