Twitter just got significantly crazier

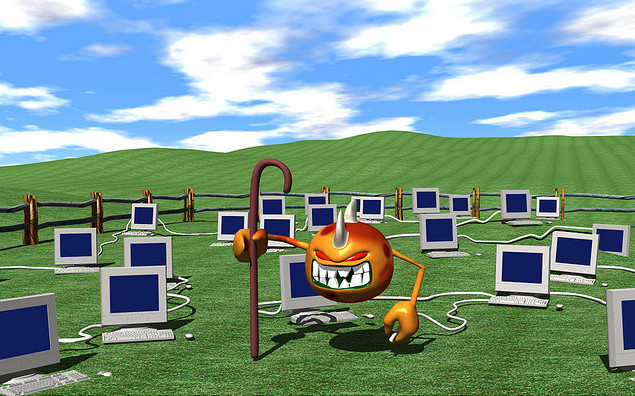

Basically, a bunch of misogynist pranksters from 4chan have recently taken to creating fake Twitter accounts to impersonate feminist caricatures. This campaign in turn seems to be part of a broader effort, according to this Buzzfeed summary, “Activists Are Outing Hundreds Of Twitter Users Believed To Be 4chan Trolls Posing As Feminists”:

Operation: Lollipop is a propaganda campaign run largely by members of the Men’s Rights and Pick-Up Artist communities. The idea is to pose as women of color on Twitter and guide activist hashtags as a way to embarrass the online social justice community.

This loathsome and ridiculous development raises all sorts of disturbing questions — particularly for journalists who increasingly rely on Twitter for “person in the street” quotes and story leads. It’s good to see the pushback against these buffoons, but it’s also one more reason to use caution when relying on Twitter as a source of actual information, human sentiments, and quotations.

Personalization and its discontents

Data Doppelgängers and the Uncanny Valley of Personalization is a provocative argument by Sara Watson, in the Atlantic, about the imperfection of personalized ad-targeting and the creepy feelings it induces, with a nod to Freud:

Ads seem trivial. But when they start to question whether I’m eating enough, a line has been crossed…

My data doppelgänger is made up of my browsing history, my status updates, my GPS locations, my responses to marketing mail, my credit card transactions, and my public records. Still, it constantly gets me wrong, often to hilarious effect. I take some comfort that the system doesn’t know me too well, yet it is unnerving when something is misdirected at me. Why do I take it so personally when personalization gets it wrong?…

Personalization appeals to a Western, egocentric belief in individualism. Yet it is based on the generalizing statistical distributions and normalized curves methods used to classify and categorize large populations. Personalization purports to be uniquely meaningful, yet it alienates us in its mass application. Data tracking and personalized advertising is often described as “creepy.” Personalized ads and experiences are supposed to reflect individuals, so when these systems miss their mark, they can interfere with a person’s sense of self. It’s hard to tell whether the algorithm doesn’t know us at all, or if it actually knows us better than we know ourselves. And it’s disconcerting to think that there might be a glimmer of truth in what otherwise seems unfamiliar. This goes beyond creepy, and even beyond the sense of being watched.

We’ve wandered into the uncanny valley.

Obama <3 Anonymous

Obama Adviser Valerie Jarrett: President Has ‘Cabin Fever’:

“I might walk up to the Lincoln Memorial, sit on there,” Obama said when asked on the “Live with Kelly and Michael” talk show what he would choose if he could do anything unrecognized. “Maybe I’d wander around and find myself at a little outdoor cafe or something and sit and order something and just watch people go by. The thing you miss most about being president is anonymity.”

Before you laugh, remember that the presidential panopticon seems to be where everyday life for the rest of us is heading.

Of course, there’s always the Henry V “go incognito amongst your troops the night before battle” solution:

Gawker anatomized

Great description of Gawker in Michael Hastings’ posthumously published novel, as quoted in Dwight Garner’s review:

…Wretched, a website that resembles Gawker. It’s a site he admires and reviles, where the contributors harbor “a desire to be noticed and to criticize the criticizers of the world, to gain its acceptance by rejecting it, breeding a strange kind of apathy and nihilism and ambition.”

There is, I think, a direct line of descent — ideologically, at least — from Spy to Suck.com to Gawker.

Requiem for a copywriter

Requiem for a copywriter

Ad man Julian Koenig created Volkswagen’s classic “Think Small” campaign, which must have left a deep impression on the young Steve Jobs. This obit for Koenig, who also created memorable campaigns for Timex and the first Earth Day, is full of fascinating bits.

In 1966, he was inducted into the Copywriters Hall of Fame of the Advertising Writers Association of New York. He expressed his gratitude by skewering the association for giving awards based on creativity or artfulness.

Sales, he suggested, were the only important measure.

“The hardest thing in the world to resist is applause,” he said at his induction. “Your job is to reveal how good the product is, not how good you are, and the simpler the better.”

…Advertising earned Mr. Koenig a very good living, and it was important to him that he received proper credit for his work. But throughout his life he also questioned whether it was a valid profession.

He spoke candidly about his concern in a 2009 interview for the public radio program “This American Life.” The segment was produced by [his daughter] Sarah Koenig, a “This American Life” producer.

“Advertising is built on puffery — on, at heart, deception,” he said. “And I don’t think anybody can go proudly into the next world with a career built on deception — no matter how well they do it.”

I thought I came late to John Darnielle and the Mountain Goats. By the time I discovered them in 2004, they already had a dauntingly extensive catalog of tapes and albums under their belt. But it turned out to be good timing: they were on the cusp of a creative leap. Now I’ve been a fan for a decade (previous posts

I thought I came late to John Darnielle and the Mountain Goats. By the time I discovered them in 2004, they already had a dauntingly extensive catalog of tapes and albums under their belt. But it turned out to be good timing: they were on the cusp of a creative leap. Now I’ve been a fan for a decade (previous posts