Berkeley J-School’s Chronicle panel: The horse-and-buggy set’s lament

[Warning — long post ahead! This happens when one has a transcontinental flight during which to blog.]

A panel at the UC Berkeley School of Journalism that I attended yesterday evening was titled “The SF Chronicle in Transition.” “Transition,” here, is plainly a euphemism; the title ought to have been “The Chronicle In Extremis,” and the mood was that of a wake.

There is plenty of cause for communal handwringing in the face of the wrenching cutbacks and shutdowns that are plaguing newspapers across the U.S. and that most recently have threatened the survival of our major Bay Area daily, which has reportedly been losing its owner, the Hearst Corporation, $50 million a year, and looks likely to cut its staff by half if owners and unions reach an agreement. If not, Hearst has threatened to shut the paper down, leaving this city without a major daily newspaper. (It’s hard to believe that Hearst would simply write off its huge investments in the Chron, however; the threat sounds more like a negotiating tactic than a serious option.)

The panel offered a by now familiar litany, a mixture of wrongheaded cliches with legitimate fears. Heard, for instance, was the old canard that giving up newspapers for the Web means we won’t ever stumble on things we didn’t know we were interested in. (In fact, hugely popular sites like Boing Boing or Kottke.org have professionalized the generation of serendipity, and our Twitter friends feed us as varied a diet of links as we choose to feast on.) Here was the routine complaint about rudeness and “uninformed shouting” in comments forums. (A brief shouting match between one member of the crowd at the Berkeley event and the editor and publisher of the Berkeley Daily Planet — from what I could hear, about whether a writer had been censored — was as rude and off-topic as anything I’ve seen in a newspaper comments section.)

Beyond the usual Web-bashing lay some realistic worries about how we’ll get our local news and who will perform the public-interest watchdog role if newspapers vanish. “We’re in for a real dangerous period where there’s no one watching the store,” Lowell Bergman, the veteran investigative reporter, predicted.

“Stealing MySpace” review in Washington Post

It’s been about a decade since I did my last book review for the Washington Post, of a Marshall McLuhan biography, so it was time for a return engagement, I guess! Yesterday’s Post featured my review of Wall Street Journal reporter Julia Angwin’s new book on the story of MySpace. (Here’s the book’s site.)

The book is very thorough, dogged business reporting, worth reading if you want to know about MySpace’s origins in the murk of the Web’s direct-marketing demimonde or if you’re interested in the corporate maneuvering around Rupert Murdoch’s 2005 acquisition of the company. It offers only some brief glimpses of the culture of MySpace, though, and I think MySpace is more interesting for the vast panorama of human behavior it provides than for its limited innovations as a Web company or for the ups and downs of its market value. Here’s the review’s conclusion:

Angwin tries to cast MySpace as “The first Hollywood Internet company” — freewheeling, glitzy, “where crazy creative people run the show” — in contrast to what I guess we’d have to call the Internet Internet companies, like Silicon Valley-based Facebook, where programmers rule the roost. But that’s a bit of a false distinction: Programmers can be crazily creative people, too, and plenty of creative types have learned to master technology. (See, for example, Pixar.)

You can’t help getting the impression from “Stealing MySpace” that MySpace’s founders, however smart and dogged they may have been, were also opportunists who simply got lucky. That leaves us wondering about the wisdom of Murdoch’s acquisition. Facebook surpassed MySpace long ago in innovation, buzz and, more recently, actual traffic, according to some tallies. It has thereby stolen MySpace’s claim to being “most popular” and rendered Angwin’s subtitle obsolete.

Sic transit gloria Webby. Was Murdoch’s purchase of MySpace a savvy coup or just a panicked act of desperation, like Time Warner’s far more costly AOL mistake? It will take at least a few more years before we know for sure. By then, no doubt, both MySpace and Facebook will have been elbowed aside by some newcomer nobody has heard of today.

Shirky sets the wayback machine to 1500

Clay Shirky has a new post up titled “Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable” that is really about as cogent a summary of the state of affairs in the land of dying newspapers as you’re likely to find. Here are a couple of brief excerpts, but I highly recommend reading the whole thing:

When someone demands to be told how we can replace newspapers, they are really demanding to be told that we are not living through a revolution. They are demanding to be told that old systems won’t break before new systems are in place. They are demanding to be told that ancient social bargains aren’t in peril, that core institutions will be spared, that new methods of spreading information will improve previous practice rather than upending it. They are demanding to be lied to.

There are fewer and fewer people who can convincingly tell such a lie….

Print media does much of society’s heavy journalistic lifting, from flooding the zone — covering every angle of a huge story — to the daily grind of attending the City Council meeting, just in case. This coverage creates benefits even for people who aren’t newspaper readers, because the work of print journalists is used by everyone from politicians to talk radio hosts to bloggers. The newspaper people often note that newspapers benefit society as a whole. This is true, but irrelevant to the problem at hand; “You’re gonna miss us when we’re gone!†has never been much of a business model. So who covers all that news if some significant fraction of the currently employed newspaper people lose their jobs?

I don’t know. Nobody knows. We’re collectively living through 1500, when it’s easier to see what’s broken than what will replace it. The internet turns 40 this fall. Access by the general public is less than half that age. Web use, as a normal part of life for a majority of the developed world, is less than half that age. We just got here. Even the revolutionaries can’t predict what will happen.

J-schools: from phone and typewriter to Web

There’s a great back-and-forth in the comments on my post below about new media skills and journalism schools.

As my former colleague Damien Cave says, journalism schools ought to be teaching students to ask, “What’s the best way to tell this story?” and to become adept at finding, and executing, an answer.

Plainly some students want more of a new-media focus than they’re getting. There’s an interesting contrast between what some of the recent Columbia grads posting are saying (in essence, that the school isn’t really keeping up) with what faculty member Paula Span says (they’re working like crazy to keep up). Maybe the incoming students today are getting a different experience from their recent predecessors. Schools don’t change as fast as the Web does.

“Cranky” asked me, “Universities are not vocational schools. Where did you learn your Web skills, Scott? On the job, right? Just the way it should be.” It’s sort of a moot question in my case, since the Web didn’t exist when I was in school. But I didn’t expect the university to teach me to type, either, so point well taken.

I agree with those (including, I guess, Lemann himself) who say that a journalism school shouldn’t be in the business of teaching technical skills. But I would always have expected any professor teaching me about writing to be familiar with the experience of typing, and understand how the process of typing affects the form and function of producing journalism. Similarly, you would expect someone teaching reporting, then and now, to understand the telephone and its role in putting a story together. You didn’t need to know the technical underpinnings of the phone system then, any more than you need to know how to program Flash now. But you needed to understand how to make a call, and how the phone fit into your journalist’s job of story-finding-and-communicating, just as you now need to understand how different forms of Web communication fit into that same job today.

We do not expect journalism professors to be programmers. But I think we have a right to expect them to be conversant in the media universe in which their students will be working. To teach journalism and still be ignorant of today’s Web would be like teaching journalism 30 years ago while being ignorant of the typewriter and the telephone. You still might have some wisdom to impart to your students, but you’d be operating at a significant remove from the real world in which the craft is practiced.

The passion of Jim Cramer

By now the entire Internets have witnessed the extraordinary performance on Jon Stewart yesterday, in which Jim Cramer, the bug-eyed host of CNBC’s Mad Money show, took withering, and deserved, shots about his, and his network’s, participation in the market’s recent massive failure. (TPM has the whole thing up here if you want to watch it again.)

By now the entire Internets have witnessed the extraordinary performance on Jon Stewart yesterday, in which Jim Cramer, the bug-eyed host of CNBC’s Mad Money show, took withering, and deserved, shots about his, and his network’s, participation in the market’s recent massive failure. (TPM has the whole thing up here if you want to watch it again.)

For me the high point came towards the end, with Stewart calling Cramer on the investing hucksterism that has been standard fare on CNBC for so long:

I understand you want to make finance entertaining, but it’s not a fucking game… Selling this idea that you don’t have to do anything — any time you sell people the idea that, sit back and you’ll get 10 or 20 percent on your money, don’t you always know that that’s gonna be a lie? When are we gonna realize in this country that our wealth is work, that we’re workers, and by selling this idea of, hey man, I’ll teach you to be rich, how is that different from an infomercial?

Cramer spends most of the lengthy interview admitting failure and hanging his head. I give him credit for showing up — something that ludicrous grandstander Rick Santelli couldn’t bring himself to do — even though I found his rationalizations mostly unconvincing.

Watching Cramer’s show, which I have only rarely done, has always been a bizarrely alienating experience for me. I got to know the host three decades ago when we both worked at the American Lawyer magazine, Steve Brill’s feisty startup. (I recently wrote a bit about that experience.) I was a callow summer intern, Cramer was a hard-working reporter, and he was extraordinarily generous and helpful to me. I learned a lot from him about how the work of investigative reporting is done. He was clearly an intense and driven guy who seemed to require very little sleep. But, with me at least, he was also for real.

On TV these days, of course, he is anything but. He presents a strange caricature of the addled, hyper-reactive Wall Street lunatic. Since I knew Cramer under other circumstances, I have always assumed that this was a persona, a dramatic construct, a Brechtian parody of the personality of capitalism — and a daily illustration of the “greater fool” theory.

Maybe that’s giving Cramer the benefit of too much doubt; but it does seem hard to miss that the show is intended as comedy. Do people actually make investment decisions by listening to a man who (as Stewart puts it) “throws plastic cows through his legs shouting ‘Sell, sell, sell!’ “? And if they do, should Cramer at least share with them the blame for losses resulting from such gullibility?

I don’t know. But I do know that if you play a role long enough, you become the part. (As I recall, Vonnegut’s Mother Night has something to say about this. Also, in a different vein, Kurosawa’s Kagemusha.) In his Jon Stewart appearance, I thought I saw glints of the real Cramer poking through the madman act. But at this stage of the show, they’re pretty faint.

Columbia J-School walks backward onto the Web

Eye-opening New York mag piece on a rift at the Columbia Journalism School as it struggles with the concept of “new media”: The current faculty doesn’t have the skills in digital storytelling that (some of) the school’s leadership wants to teach. Hiring adjuncts costs a lot of money. So they’re considering crash courses for the professors. And it sounds like they’re still ambivalent. This quotation from the school’s dean, Nick Lemann, deserves some unpacking:

“You can go to the Learning Annex and take a Flash course. I don’t think what we should do is be replicating courses you can take at the Learning Annex. But you have to have some familiarity, or you’re not able to execute a website.”

This straw man is so lightweight it’s amazing it didn’t evaporate as Lemann spoke it. The Learning Annex has a pretty extensive curriculum, you know; they’ll teach you writing and reporting too. All the basic skills that Columbia Journalism School teaches can be learned at extension schools and night schools and in the school of one’s own pajamas. The value the school presumably offers is in how it teaches writing (and photography and, one hopes now, online journalism): not just the basics of accuracy and clarity and economy of expression — the nuts and bolts of reporting and writing — but the ethics and the thoughtfulness and the passion. Right?

Columbia presumably understands that this is its job when it comes to teaching traditional newspaper and broadcast reporting. But suddenly, when the skills involved are newfangled Webby things, that job becomes discounted, something anybody can learn from any old extension school, or any faculty member can pick up by cramming.

Of course these journalism professors should familiarize themselves with the tools if they haven’t already. But you wouldn’t want to try to learn the soul of the discipline from a newbie, would you? Any more than Columbia would ask someone who’d just written their first headline to teach basic news editing. The roster of Columbia faculty is an impressive list, but they are mostly veterans of an era that is fading today, and it is unfair to both them and their students to expect them to become overnight experts in a new world that most of us are just beginning to understand.

The condescension on display toward new media forms here is a recapitulation of what the pioneers in photojournalism encountered in the early days of that field, when it was more technically forbidding but hardly seemed like a serious part of covering a story. Today, one hopes any serious journalism educator understands that learning photojournalism is a lot more than just acquiring the technical facility of taking a decent shot. Similarly, the business of learning to use different online media forms to tell a story goes way beyond just “taking a Flash course.”

We need journalism schools like Columbia to take the journalistic traditions that they have long preserved and carry them forward into the digital age. But they will not be able to play that role until they take these new media forms seriously. The New York piece describes the school’s efforts to begin to integrate digital-era skills with its basic curriculum. That’s promising. But if it’s serious about this, it needs to hire people who know Web journalism as thoroughly as the current faculty knows the journalism of previous eras.

Why is the Journal flubbing its biggest story ever?

You’d think that the Wall Street Journal would own the biggest story of the past year, the meltdown of capitalism-as-we’ve-known-it. But the paper’s coverage has lagged. It did good work on the collapse of Bear Stearns a year ago, but for the most part it has done a mediocre job of explaining all that has gone wrong with our economic system. It has been left to the marquee names at the paper’s biggest competitor, the New York Times, to help us begin to understand where we are and how we got here: writers like Joe Nocera, Gretchen Morgenson, David Leonhardt, Floyd Norris, and of course Paul Krugman. Their pieces — like, for instance, Nocera’s explanation of where those billions we’re shoveling at AIG are really going — have regularly been essential reading, whereas the Journal’s coverage just hasn’t risen to that level too often.

One can think of several possible explanations for this failure. For one thing, the Wall Street collapse represents not only a story on the Journal’s home turf but also the disintegration of its motivating vision. The paper that champions “free people and free markets” is, I think, having a hard time coming to terms with the fact that free markets have just failed free people in a very big way. It has also, I imagine, been hard for the Journal’s troops to concentrate as they undergo a wrenching change of ownership and begin to adjust to new marching orders from the Murdoch regime.

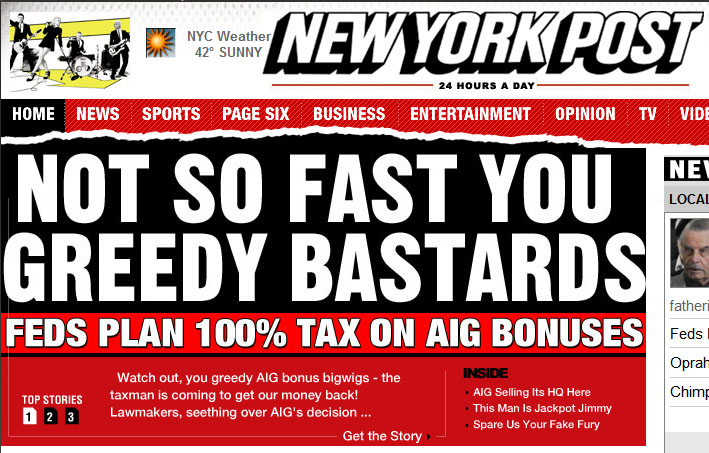

![]() Still, it seems very wrong-headed that, at the precise moment the Journal ought to be (pardon the usage) capitalizing on its strength in in-depth financial coverage, it is instead distracting itself with an effort to become a sort of upscale USA Today (with utterly superfluous features like a new sports section).

Still, it seems very wrong-headed that, at the precise moment the Journal ought to be (pardon the usage) capitalizing on its strength in in-depth financial coverage, it is instead distracting itself with an effort to become a sort of upscale USA Today (with utterly superfluous features like a new sports section).

In Mother Jones, former Journal reporter Dean Starkman asks “How Could 9,000 Business Reporters Blow It?” One suggestion is that the Journal’s tradition of attending to the colorful titans of the business world became a liability in covering an impersonal credit crisis:

Jesse Eisinger, a former financial columnist for the Journal and now a senior writer for Portfolio, says the paper, like business journalism generally, clung to outdated formulas. Wall Street coverage tilted toward personality-driven stories, not deconstructing balance sheets or figuring out risks. Stocks were the focus, when the problems were brewing in derivatives. “We were following the old model,” he says.

Where did that old model come from? Monday’s Journal happened to carry a review of a new book by former Journal exec Richard Tofel — a biography of Barney Kilgore, the legendary editor who made the Journal what it is today (or, rather, what it was till recently).

Kilgore believed in humanizing articles on even complicated subjects, insisting that editors and writers try to make room in news stories, whenever possible, for anecdotes, narrative details and portraits of individuals, thus bringing topics alive for that “average reader.”

So was it Kilgore’s fault the Journal failed to offer early insight into the real estate crisis, derivatives, the instability of the banking system, and so on? We can’t blame him exclusively for that; the approach credited to him is one that is nearly universal in journalism today. The reasons behind the Journal’s weak showing in the current crisis seem of more recent vintage.

Still, there’s a lesson here in the limits of the daily journalism world view. Sometimes the heart of the story lies beyond “one person’s tale.” Sometimes, as Felix Salmon’s fascinating piece in the latest Wired — The Formula That Killed Wall Street — shows, it lies with a mathematical insight. Sometimes we need to turn to demographics, or history, or science.

Reading the Journal’s review of the Kilgore book, I did get an odd feeling that there was some elephant-in-the-room avoidance going on. Both review and book laud the man who shaped the modern Wall Street Journal at the very moment that new owners are radically altering, if not dismantling, that institution. Yet the review did not even offer a tip of a hat or wink of an eye to that fact.

It’s not easy to write about change at a newspaper in the pages of that newspaper, but it’s one of the things we expect our independent press to be able to handle when the occasion arises. This occasion is one that appears to have been handled by sheer ostrich-like avoidance.

Reverse market psychology

The wisdom of Wall Street has it that the market never hits bottom until the last bull capitulates. In other words, there is no hope of things turning around until everyone has given up hope of things turning around.

If this is true, then this morning’s Wall Street Journal lead story ought to give us hope, because it reports a bleak absence of hope.

“Investors around the globe appeared to be giving up hope and girding for a prolonged recession.”

I thought it’s been crystal clear since last September, if not before, that the “prolonged recession” scenario was the best case. But maybe it’s been looking different to the folks on Wall Street. Maybe that’s why they’re still in trouble?

“Traders said the latest downdraft broadly reflected a deepening sense of gloom among investors. Gone are the days where the mantra among investors was to “buy the dips,” on the belief that when stock prices fall, they’re likely to rebound. Instead, the opposite sentiment has taken hold.

“It’s like an unending nightmare,” says Kent Engelke, managing director at Capital Securities Management in Glen Allen, Va.

So it sounds like the last of the bulls has thrown in the towel. Which ought to mean that we’re at or close to a market bottom.

But here is why this particular strand of Wall Street wisdom always seemed problematic to me. If it were accurate, then some portion of the market would follow it — in other words, some group of investors would always see the general rout and think, “Aha! Market bottom! Time to buy!” And those investors would be the very hope-filled buyers whose existence would indicate the market hadn’t hit bottom yet after all.

Okay, it’s not exactly Zeno’s Paradox, but it’s a flaw in the logic, yes? Not that it’s anything but an idle question, for me, at any rate. Market timing, I have always felt, is for people looking for ulcers.

Writing and rewards: an author marches on his stomach

The thing about writing a book is — pardon the obviousness — you have to write a whole lot of words.

Now, plenty of bloggers do lots of writing, over a period of six months or a year they might easily reach the 80-100,000 word sum of a typical book. There are two big differences for the author of a book: First, you’ve got to write according to a plan, so that the little bricks of words you are piling up form something coherent and shapely, whereas bloggers win a free pass to be discursive each time they hit “post.” Second, bloggers’ work is fueled by a daily reward of feedback and reaction to their posts, whether it’s an onslaught of comments or just a small jump on the site-traffic meter. Authors don’t get that. That is why, so often, we devise systems of our own — tracking systems to help keep ourselves on plan, to know whether we’re ahead or behind, and personal reward mechanisms, to provide incentives across arduous weeks and months.

My tracking system is simple: a small spreadsheet with word-count quotas and tallies. I don’t really need to do this, but the ritual of recording each day’s verbal production keeps me moving. The reward mechanism is even simpler.

I have a taste for red licorice. I grew up loving an odd Danish confection called Broadway Licorice Rolls — you got four little rolls of tape-like shapes in a plastic foil wrapping from the candy-store counter. Far as I can tell, they no longer exist. (A brand called Delfa Rolls was distributed online until recently, but is now marked discontinued.)  The closest substitute I have found is Haribo red licorice wheels. I buy them in bulk and dump a big bag in a candy jar in my office. When I’m writing a book, each day after I’ve drafted my target amount of prose — usually 1000 words, sometimes more if I’m behind — I mark the occasion with one or two of these fragrant corn-syrup-solid bonbons.

The closest substitute I have found is Haribo red licorice wheels. I buy them in bulk and dump a big bag in a candy jar in my office. When I’m writing a book, each day after I’ve drafted my target amount of prose — usually 1000 words, sometimes more if I’m behind — I mark the occasion with one or two of these fragrant corn-syrup-solid bonbons.

Now, I know what you’re thinking; or rather, I know there are two groups of you out there. One group is snorting with derision at this crude methodology — self-doping with sugar! All I can say to them is, you do whatever it takes to get the job done. The other bunch is thinking, “How do you avoid stuffing your face every time you hit a rough spot?” All I can say to them is, that would feel like cheating at solitaire. Maybe I scored when they passed out the genes for delayed gratification.

On yesterday’s Fresh Air the science writer Jonah Lehrer was describing a bit of brain research that he discusses in his new book How We Decide. Test subjects divided into two groups were asked to memorize numbers. One group was assigned two digit numbers, the other seven digit figures. Then the members of each group were offered a choice between some sort of gooey, fatty dessert and an austere fruit salad. Of course the seven-digit crew opted much more heavily for the junk food than the double-digit gang.

This result, according to Lehrer, displayed how easily the prefrontal cortex can be overtaxed. The task of remembering the longer numbers had impaired the subjects’ long-term decision-making capacity — the part of their brains that would say, “Don’t eat that crud, it’s bad for you.”

Maybe so. Lehrer has read the study and I haven’t. I only know that as I heard him describe the experiment, and before he offered his interpretation, I sat there and thought: of course the seven-digit people went for the sugar. They’d been asked to do something hard! Now they were rewarding themselves.