In 1994 Louis Rossetto cranked up HotWired and believed he was ushering in the professionalization of the Web. It was time to rout all the anarchists and the hackers and the amateurs who thought the Internet was all about self-expression (and them). “The era of public-access Internet has come to an end,” he declared. He didn’t mean that the public would no longer be able to access the Internet, of course; he was drawing an analogy to public-access TV. Just as that once-promising avenue for citizen media had been eclipsed by the pros of the cable world, so, he reasoned, the Web would similarly leave the amateurism of its youth behind.

Nick Carr believes this is still going to happen, but many of us today understand that the opportunity the Web affords all of us to add to it lies at the heart of the medium’s identity. It’s not some minor feature of the medium’s youth that will be sloughed off as maturity arrives. It’s not some incidental efflorescence of excess creativity that will vanish once the laws of supply and demand kick in. It is what makes the Web tick. You can try to ignore that, and use the Web as a mere replacement for paper and trucks, but why bother? You will lose your readers and your future.

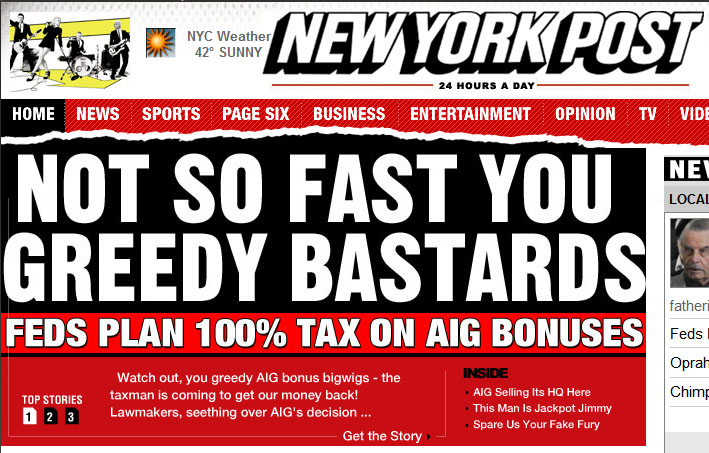

I thought of all this as I read reports today of Rupert Murdoch’s pronouncement that “The current days of the internet will soon be over.” Phrased that way, the prediction makes it sound like the end times are near. But the only apocalypse in sight, I’m afraid, is that of the old-line news industry, if it insists on pursuing dead-end subscription models for general-interest Web products.

There is money to be made on the Web for the providers of information, but it will never be made by locking away generic news and opinion articles and charging subscription fees to access them. Cutting your content off from the rest of the Web in this fashion robs it of its Webbiness. It’s like a movie producer in the 1930s saying, “Hey, let’s make talkies!”, but then turning off the sound in the theaters.

Murdoch, and any other publisher who shuts the gates, may well boost his bottom line in the short term. But in the medium term and beyond he is simply guaranteeing the slow decline and ultimate irrelevance of his publication. This is painful for journalists and media execs to hear, but they need to hear it — just as, back in 1994, Rossetto needed to hear that no, actually, “public access” was exactly what the Web was all about.