I’ve written a bit here about the curse of over-compression in recorded music:

For those of us already unhappy with the music industry’s bungling of the transition to digital distribution, here’s another thing we can blame them for. Seeking to have their products “stand out,†they entered a sonic race to the bottom… The irony is that we can only perceive loudness through contrast, so the contemporary recordings sound miasmic, not punchy. When you crank up all the dials to, as Spinal Tap would say, 11, everything sounds the same, your ears get tired, and you wonder why music doesn’t sound as good as it did when you were younger.

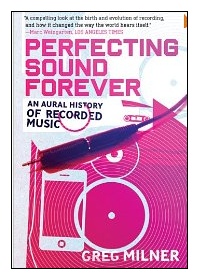

So when I discovered, belatedly, that Greg Milner has written an entire book about the birth, history and present plight of recording, I grabbed it. It’s called Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music.

If, like me, you have always cared about sound quality but never had much of a vocabulary or structure for discussing or understanding it, it’s a wonderful read.

Milner’s tale starts with Edison’s famous “sound tests” (where they’d pit live vs. recording in front of an audience) and carries through to our MP3-muddled present. It’s fascinating to see how certain threads follow us from the days of sound cylinders up to the iPod era. Each successive generation of technology promises — and, for everyday listeners, seems to deliver — the utopia of perfect, life-like sound, sound captured so well that you cannot distinguish the recording from reality. But you soon realize a truth that Milner elegantly excavates: this “reality” is a chimera — an unobtainium of the ear. Our norms for “realistic sound” are hopelessly subjective. If Victrola recordings that crackle in our ears today sounded like “reality” to 1920s listeners, what will music-lovers of the 2120s think about the over-compressed recordings our culture is now producing?

There’s so much that’s fun and unexpected in Perfecting Sound Forever: the early religious wars between the proponents of acoustic recording and believers in the electrical approach that won out (presaging today’s analog vs. digital argument); how the advent of recording tape began to move us from the notion of sound reproduction to the idea of composing in the studio; how competition between radio stations upped the compression ante until we reached the point where the Red Hot Chili Peppers became “the band that clipped itself to death”; and much more.

Music criticism has fallen on hard times today, what with the fragmentation of the audience and the collapse of the industry. But Milner’s book is one case where writing about music most certainly isn’t like dancing about architecture — it’s more like dancing with ideas. Here’s a taste:

We never fully agree on what perfect sound is, so we keep trying, defining our sonic ideals against those of others, playing the game to the best of our abilities, in whatever position we occupy on the field. We add more reverb, we pump up the bass, we boost the treble, we compress dynamic range, we send the band back into the studio because we don’t hear a single — and we then remix that single, we press the song on vinyl, on disc, as a ghostly collection of ones and zeros that we send around the world. We do what we can to make it sound right and then we hear the sound flow from the speakers and we call it perfect.

With this post I intend to begin more regularly reviewing the books I’m reading, right here on Wordyard. Because, as my friend Laura Miller keeps reminding us, readers are scarcer than writers — or, as Gary Shteyngart was just saying on Fresh Air, “Nobody wants to read but everybody wants to write.”

Well, I intend to keep doing both! And, just so you know, I will also be wiring up my links to Amazon with partner codes; these will funnel a tiny bit of change back to me so I can keep buying those books.