The journalism industry ships lemons every day. Our newsrooms have a massive quality control problem. According to the best counts we have, more than half of stories contain mistakes — and only three percent of those errors are ever fixed.

Errors small and large litter the mediascape, and each uncorrected error undermines public trust in news organizations. In Pew’s last survey in Sept. 2009, only 29 percent of Americans believed that the press “get the facts right.”

Yet the tools and techniques to fix this problem are known and simple. I’ve been working in this area for the last two years. Here’s a distillation of what I’ve learned: three basic steps any online news organization can take today to tighten quality control, reduce errors and build public trust.

-

Link generously

- Read more on the value of links: In Defense of Links.

A piece without links is like a story without the names of its sources. Every link tells a reader, “I did my research. And you can double-check me.”

- Show your work

- Read a longer argument for the value of versioning.

Or try out the WordPress plugin.

The news isn’t static, and online stories don’t have to be, either. Every article or post can and should be improved after it’s published. Stay accountable and transparent by providing a “history” of every version of each story (a la Wikipedia) that lets readers see what’s changed.

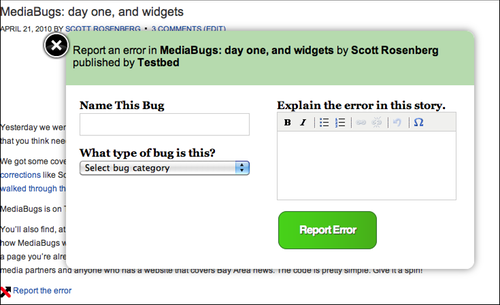

- Help people report your mistakes

- Get some report an error buttons at the Report an Error Alliance.

Or use the MediaBugs widget.

The Internet is a powerfully efficient feedback mechanism. Yet many news organizations don’t use it. Put a report-an-error button on every story: It tells readers you want to know when you’ve goofed. Then pay attention to what they tell you.

Why aren’t these practices more widely adopted? Here are four reasons:

(1) Workflow and tools: In many newsrooms, especially those still feeding print or broadcast outlets, it’s still way too hard to fix errors or add links to a story for its Web edition. And content-management systems don’t yet offer corrections and history tools “out of the box.”

(2) Denial and avoidance: Other people make errors. Many editors and reporters don’t believe the problem is serious, or think it doesn’t apply to them. And most don’t understand how badly their Web feedback loop is broken.

(3) Fear of readers: Many journalists view readers as adversaries. The customer they feel they’re serving is an abstraction; the specific reader with a complaint is “someone with an agenda” whom they have a duty to ignore.

(4) Where’s the money? Many media companies are in financial free-fall. Correction systems and trust-building tools don’t bring in revenue directly, and they eat up product-development time and money.

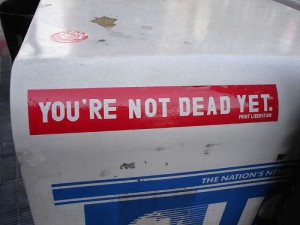

These are serious obstacles. But journalists will never regain public trust unless we overcome them.

Ask journalists what sets them apart from everyone else sharing information online and we’ll say: We care about accuracy. We correct our mistakes. In a changing media economy that’s challenging the survival of our profession, we need to follow through on those avowals. Otherwise, we shouldn’t be surprised when Pew’s next biennial survey of public trust in the media shows even more dismal results.

[Crossposted from PBS MediaShift Idea Lab. This edition employs all three techniques I mention.]