I’m having flashbacks these days, and they’re not from drugs, they’re from the rising chorus of media-industry froth about how Apple’s forthcoming iPad is going to save the business of selling content.

I’m having flashbacks these days, and they’re not from drugs, they’re from the rising chorus of media-industry froth about how Apple’s forthcoming iPad is going to save the business of selling content.

Let me be clear: I love what I’ve seen of the iPad and I’ll probably end up with one. It’s a likely game-changer for the device market, a rethinking of the lightweight mobile platform that makes sense in many ways. I think it will be a big hit. In the realm of hardware design, interface design and hardware -software integration, Apple remains unmatched today. (The company’s single-point-of-failure approach to content and application distribution is another story — and this problem that will only grow more acute the more successful the iPad becomes.)

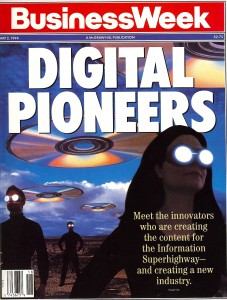

But these flashbacks I’m getting as I read about the media business’s iPad excitement — man, they’re intense. Stories like this and this, about the magazine industry’s excitement over the iPad, or videos like these Wired iPad demos, take me back to the early ’90s — when media companies saw their future on a shiny aluminum disc.

If you weren’t following the tech news back then, let me offer you a quick recap. CD-ROMS were going to serve as the media industry’s digital lifeboat. A whole “multimedia industry” emerged around them, complete with high-end niche publishers and mass-market plays. In this world, “interactivity” meant the ability to click on hyperlinks and hybridize your information intake with text, images, sound and video. Yow!

There were, it’s true, a few problems. People weren’t actually that keen on buying CD-ROMs in any quantity. Partly this was because they didn’t work that well. But mostly it was because neither users nor producers ever had a solid handle on what the form was for. They plowed everything from encyclopedias to games to magazines onto the little discs, in a desperate effort to figure it out. They consoled themselves by reminding the world that every new medium goes through an infancy during which nobody really knows what they’re doing and everyone just reproduces the shape and style of existing media forms on the new platform.

You can hear exactly the same excuses in these iPad observations by Time editor Richard Stengel. Stengel says we’re still in the point-the-movie-camera-at-the-proscenium stage. We’re waiting for the new form’s Orson Welles. But we’re charging forward anyway! This future is too bright to be missed.

But it turned out the digital future didn’t need CD-ROM’s Orson Welles. It needed something else, something no disc could offer: an easy way for everyone to contribute their own voices. The moment the Web browser showed up on people’s desktops, somewhing weird happened: people just stopped talking about CD-ROMs. An entire next-big-thing industry vanished with little trace. Today we recall the CD-ROM publishing era as at best a fascinating dead-end, a sandbox in which some talented people began to wrestle with digital change before moving on to the Internet.

It’s easy to see this today, but at the time it was very hard to accept. (My first personal Web project, in January 1995, was an online magazine to, er, review CD-ROMs.)

The Web triumphed over CD-ROM for a slew of reasons, not least its openness. But the central lesson of this most central media transition of our era, one whose implications we’re still digesting, is this: People like to interact with one another more than they like to engage with static information. Every step in the Web’s evolution demonstrates that connecting people with other people trumps giving them flashy, showy interfaces to flat data.

It’s no mystery why so many publishing companies are revved up about the iPad: they’re hoping the new gizmo will turn back the clock on their business model, allowing them to make consumers pay while delivering their eyeballs directly to advertisers via costly, eye-catching displays. Here’s consultant Ken Doctor, speaking on Marketplace yesterday:

DOCTOR: Essentially, it’s a do-over. With a new platform and a new way of thinking about it. Can you charge advertisers in a different way and can you say to readers, we’re going to need you to pay for it?

Many of the industry executives who are hyping iPad publishing are in the camp that views the decision publishers made in the early days of the Web not to charge for their publications as an original sin. The iPad, they imagine, will restore prelapsarian profit margins.

Good luck with that! The reason it’s tough to charge for content today is that there’s just too much of it. People are having a blast talking with each other online. And as long as the iPad has a good Web browser, it’s hard to imagine how gated content and costly content apps will beat that.

You ask, “What about the example of iPhone apps? Don’t they prove people will pay for convenience on a mobile device?” Maybe. To me they prove that the iPhone’s screen is still too small to really enjoy a standard browser experience. So users pay to avoid the navigation tax that browser use on the iPhone incurs. This is the chief value of the iPad: it brings the ease and power of the iPhone OS’s touch interface to a full-size Web-browser window.

I can’t wait to play around with this. But I don’t see myself rushing to pay for repurposed paper magazines and newspapers sprinkled with a few audio-visual doodads. That didn’t fly with CD-ROMs and it won’t fly on the iPad.

Apple’s new device may well prove an interesting market for a new generation of full-length creative works — books, movies, music, mashups of all of the above — works that people are likely to want to consume more than once. But for anything with a shelf-life half-life — news and information and commentary — the iPad is unlikely to serve as a savior. For anyone who thinks otherwise, can I interest you in a carton of unopened CD-ROM magazines?