I attended the Horace Mann School in Riverdale, N.Y., from 1971 to 1977. I’ve generally thought well of the school as a great environment for a brainy, socially awkward kid like me to learn and grow. I became a writer largely based on my experience there, I learned to love journalism there, and I learned almost as much from my peers as I did from my teachers.

I attended the Horace Mann School in Riverdale, N.Y., from 1971 to 1977. I’ve generally thought well of the school as a great environment for a brainy, socially awkward kid like me to learn and grow. I became a writer largely based on my experience there, I learned to love journalism there, and I learned almost as much from my peers as I did from my teachers.

Horace Mann was, plainly, a place of great privilege. (My parents paid a fortune to send me there, and I remain deeply grateful for that.) I took a crazy-long trip each day from my central Queens home to the northwest corner of the Bronx to attend. I did that because the school embraced unorthodox teachers who inspired students. Also because it made ample room for the weird kids. It helped them find other weird kids to share their weird alienation and feel a little less alienated.

Now there’s this. The article is, I believe, thoughtful, fair, and sensitive. The author is a few years younger than I am, but his account accurately reflects the school I remember.

Except, of course, for the part about a decades-spanning pattern of sexual abuse of students by teachers, a pattern that it seems the school largely ignored and that I knew essentially nothing of during my student years.

I’m not a victim myself. I experienced no molestation, or anything even borderline or ambiguous, during my six years at H.M. Still, in the wake of this article, I find myself spending a lot of time and thought re-examining my own past — as I’m guessing are the great majority of my classmates and everyone else who had anything to do with the school in those years. (There have already been extraordinary conversations both in private e-mail and in the public comments on the Times story, and they’ve challenged my assumptions and stretched my thinking on the matter.)

So here’s what i’d say if I could punch a hole in time and send a message to myself on the day, almost exactly 35 years ago, that I graduated from Horace Mann:

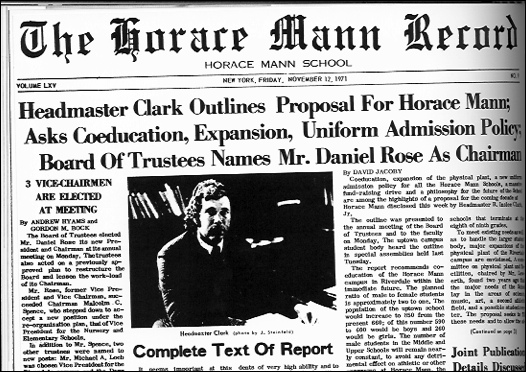

You’re not going to believe this, but 35 years from now, H.M. is going to be on the cover of the New York Times Magazine. The humongous article will tell the world, in voluminous detail and with pained concern, about a “secret history of sexual abuse” at the school. Some of the events have already happened, while you were here; most are still to come.

It’s a story about troubled people abusing power, about changing mores and standards, and also about institutional failure and betrayal. A big story, I’d say. And — sorry to break the news — but you missed it.

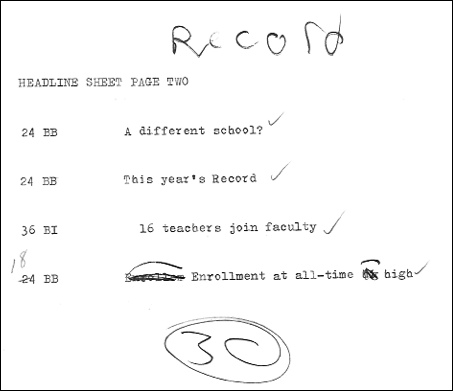

You were the editor of the Record! You and your friends prided yourselves on attempting to tell the full story of life at the school in print every week! You published exposes of pot-dealing and polled the student body of drug use and thought, in those post-Watergate years, that you were ripping the lid off the truth. But you missed something bigger and more consequential.

I guess you couldn’t have done otherwise. You’re all of 18 years old. You think you know everything — but you’re smart enough to realize how wrong you are, too.

So now that you know this, I want you to think about two lessons.

One lesson for your work: The story you think you’re living is almost never the story of your time that the future will write. For journalists this is, and should be, humbling. It should make you ask questions every time you think you’ve told the truth about a situation. What’s the next layer down? There’s always another one. Never believe you’ve gotten to the bottom of anything. Even if you’ve done a good job, the world keeps rethinking everything. And those decades-spanning changes in how we think and live are the ones will make your head explode. Expect it.

Also, one lesson for your life: Eccentricity can be inspiring. What many of your Horace Mann teachers did, with their arrogance and their mystique and the cults that some of them spun around their subjects and themselves, can be amazingly effective at persuading monkey-minded adolescents to buckle down and care about science, literature, math, Latin, or music. The cult of learning can be beautiful — but it can also be a stalking-horse for something destructive and dangerous, ugly and evil. When seductive eccentricity crosses a line into control and victimization, it becomes a curse, and it can wreck lives.

Like a lot of your teenage friends, you’ve done a pretty good job of distinguishing between these kinds of eccentricity and avoiding the kind that could hurt you. Good for you. But not everyone is as confident or as fortunate. Kids can’t reasonably be expected to draw all the lines that adults, by rights, ought to be drawing for them. It’s up to institutions like schools (and churches, businesses, and governments!) to organize themselves in a way that leaves room for creativity while protecting the participants from abuse. Power always requires accountability. There are no exceptions.

That’s hard. But it’s something adults owe the children they’re raising. Try to remember that!

And then, if I can run this conceit out one more step, I think my newly minted Horace Mann graduate self would probably say something like this in response:

Thanks for the feel-good message on graduation day! There’s not much I can do with what you’ve told me, is there? Shouldn’t you have used your time-lord powers to dump sermons on the Horace Mann trustees?

Teach me this trick and maybe I can deliver you some wisdom in your retirement home. In the meantime, I’ve got a suggestion to throw back at you.

Yeah, I do think I know everything. But I also know I’m actually still a kid. I don’t yet know who I am, but you do, right?

Forget about Horace Mann. You live 3000 miles away from the place now, anyway. You should take all this introspection and turn it on that future world you’re living in.

I know that one of the things that happens to people as they get older is that they become more willing to just go along with the patterns in their lives, to accept a “that’s the way the world is” complacency. Fight that, will you?

You can’t do anything about what happened decades ago. But look around now, in your “now.” Find the stories that are the ones that one day, you’re going to wish somebody had told sooner. Tell them.

Point and match to the 18-year-old. What could I possibly say in response to that except, “I’ll try”?

Post Revisions:

- June 9, 2012 @ 09:26:08 [Current Revision] by Scott Rosenberg

- June 9, 2012 @ 08:57:30 by Scott Rosenberg